Citizen Kane

Of his film career Orson Welles famously said that he started at the top and worked his way down. Although Bernard Herrmann’s professional trajectory was not quite so bathetic (he ended on the double-whammy of Obsession and Taxi Driver), some of the projects he worked on in his later years were little more than exploitation movies. The reputation of his first film score was to cast a long shadow over his career. When William Friedkin approached him to compose music for The Exorcist, he said to Herrmann, “I want you to give me a better score than you wrote for Citizen Kane.” Herrmann – a volatile man at the best of times – shot back, “Well, why didn’t ya make a better PICTURE than Citizen Kane?”

Of his film career Orson Welles famously said that he started at the top and worked his way down. Although Bernard Herrmann’s professional trajectory was not quite so bathetic (he ended on the double-whammy of Obsession and Taxi Driver), some of the projects he worked on in his later years were little more than exploitation movies. The reputation of his first film score was to cast a long shadow over his career. When William Friedkin approached him to compose music for The Exorcist, he said to Herrmann, “I want you to give me a better score than you wrote for Citizen Kane.” Herrmann – a volatile man at the best of times – shot back, “Well, why didn’t ya make a better PICTURE than Citizen Kane?”

A better picture than Citizen Kane is a tall order. Despite its hagiographic status (this movie isn’t just loved, it’s revered), despite the acres of film criticism that have been devoted to an analysis of its every frame, despite the legends that surround its production and its near destruction, despite the seventy years of constant projection on cinema screens, TV screens and, now iPad screens, Citizen Kane remains an astounding work.

Herrmann had worked with Welles in New York writing, arranging and conducting music for the Mercury Theatre’s radio plays (including the infamous War of the Worlds broadcast), and so, when the director moved his company out to Hollywood in 1939, it was only natural that the composer should follow them. The music that he wrote for Citizen Kane was by Hollywood standards as unconventional as Welles’s storytelling. The practitioners of film scoring at the time – composer like Max Steiner and Erich Wolfgang Korngold – were ex-pat Europeans who swathed their movies in lush romantic themes that quickly became an industry template. Just listen to Korngold’s score for The Adventures of Robin Hood or Steiner’s Gone With the Wind (1938 and 1939 respectively) to get an idea of what the Hollywood film sounded like when Herrmann arrived in Los Angeles.

Herrmann outlined his approach in a piece he wrote for The New York Times on 25th May 1941: “The movies frequently overlook opportunities for musical cues which last only a few seconds – that is, from five to fifteen seconds at the most – the reason being that the eyes usually covers the transition. On the other hand, in radio drama, every scene must be bridged by some sort of sound device, so that even five seconds of music becomes a vital instrument in telling the ear that the scene is shifting. I felt that in [Citizen Kane], where the photographic contrasts were often so sharp and sudden, a brief cue – even two or three chords – might heighten the effect immeasurably.”

Of the thirty seven cues that appear on the Varese Sarabande CD (VSD-5806) twenty one of them run for less than a minute, and the shortest (“Thanks”) clocks in at a mere eight seconds. The music is an eclectic mix of background score and source music that includes galops, polkas, waltzes, opera and jazz, making it – in the composer’s own words – “like a jigsaw”. The brooding theme that accompanies the opening montage of a decayed Xanadu and a dying Kane could come from a horror film. It is the sound of decay and corruption and is achieved through an orchestration of low wind instruments that would become one of Herrmann’s trademark sounds. The stand-out piece of the score, however, is the four minute aria Herrmann composed for the fictitious opera Salaambo. This was composed before the film was shot and Welles blocked and filmed the scene to the music.

As a listening experience the full soundtrack of Citizen Kane is by necessity something of a disjointed affair. If you’re not a completist – someone who needs to hear every note of every cue – then the score is best experienced in a suite conducted by Charles Gerhardt for RCA disc The Classic Film Scores of Bernard Herrmann. This 1974 recording includes a stunning interpretation of the Salaambo aria by Kiri Te Kanawa, and the whole piece manages to encapsulate the shifting tones of the movie in just under fourteen minutes.

Herrmann reworked themes from the film into a concert piece called Welles Raises Kane, but, as the composer admits, they are “freely developed and not used in the manner employed in the [film]“. I’m listening to this piece as I write this. It’s available on Bernard Herrmann Welles Raises Kane / The Devil & Daniel Webster / Obsession on the Unicorn Kanchana label (UKCD 2065).

The Devil and Daniel Webster

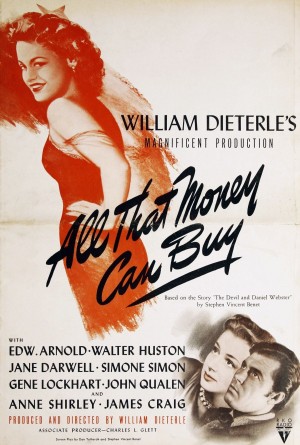

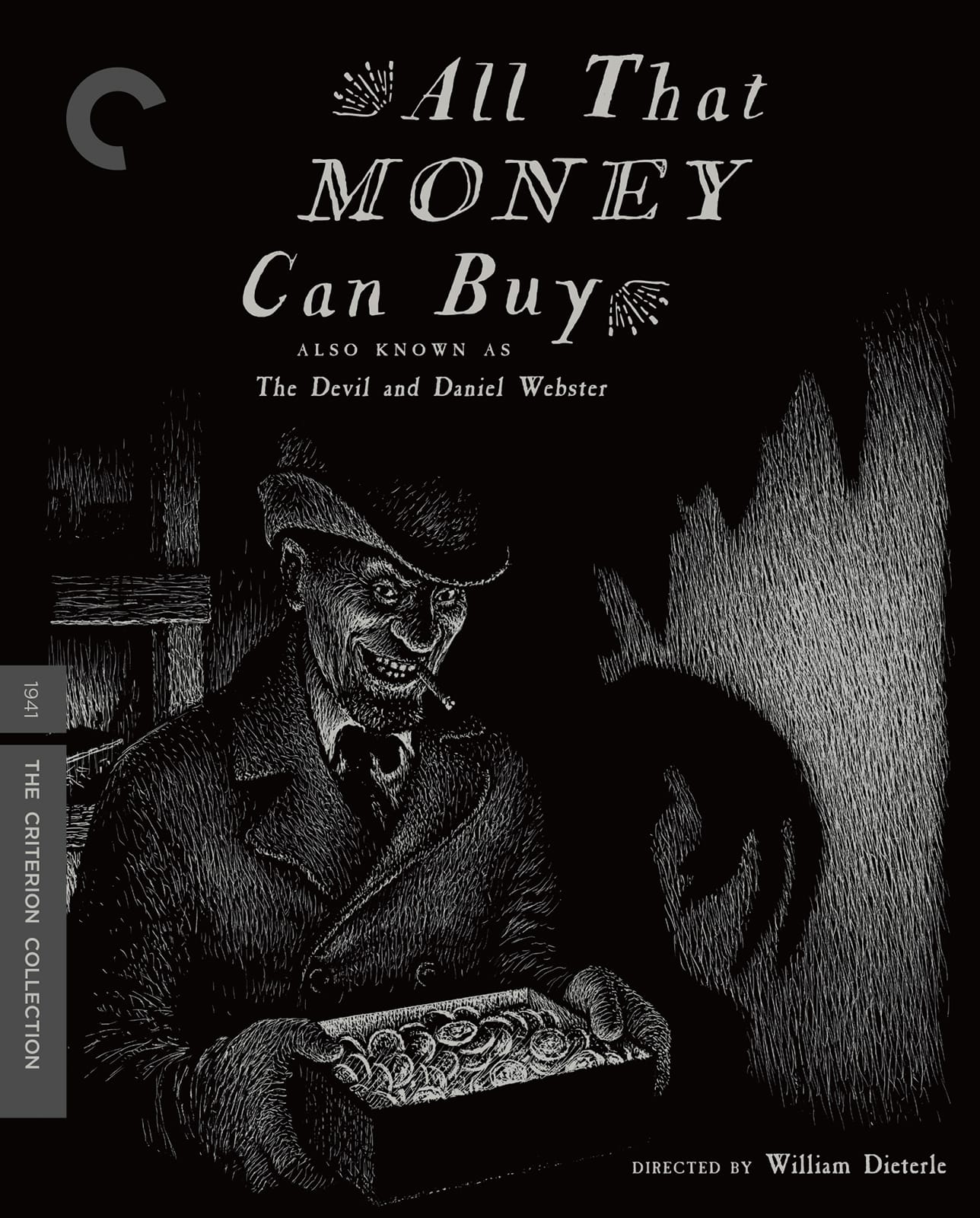

Herrmann’s second score won him his first and only Academy Award (he received two posthumous nominations in the same year -1976 – for Obsession and Taxi Driver, but lost out to Jerry Goldsmith’s demonic choral work for The Omen). The Devil and Daniel Webster was based on a short story of the same name by Stephen Vincent Benet, but had its title changed to the less evocative All That Money Can Buy on release. It is ironic that Herrmann’s feted score has not been re-recorded in full. The composer arranged the material for concert performance in 1943 and this twenty minute suite – which I’m listening to right now – is available on a Unicorn disc (UKCD 2065).

Herrmann’s second score won him his first and only Academy Award (he received two posthumous nominations in the same year -1976 – for Obsession and Taxi Driver, but lost out to Jerry Goldsmith’s demonic choral work for The Omen). The Devil and Daniel Webster was based on a short story of the same name by Stephen Vincent Benet, but had its title changed to the less evocative All That Money Can Buy on release. It is ironic that Herrmann’s feted score has not been re-recorded in full. The composer arranged the material for concert performance in 1943 and this twenty minute suite – which I’m listening to right now – is available on a Unicorn disc (UKCD 2065).

Herrmann wrote the score back to back with Citizen Kane, and he himself acknowledged that Daniel Webster was more effective as a “separate hearing” away from the movie. Perhaps this was the reason the Academy preferred it over Kane. As the original story’s title suggests, the music is underpinned with a demonic tone, especially in the two minute Sleigh Ride cue which includes sleigh bells and a sound like a cracking whip. In the movie Walter Huston plays Mr Scratch not as the Devil of the Bible, but as the American incarnation of Old Nick – a familiar figure in works as diverse as Nathaniel Hawthorne’s Young Goodman Brown, Ray Bradbury’s Something Wicked This Way Comes and even the Charlie Daniels Band’s The Devil Went Down to Georgia.

Herrmann incorporated a fiddle reel into the score and to create a sense of demonic virtuosity had a violinist play the piece multiple times in different fashions. He then stitched them together to produce an impossible performance. This was an early example of how Herrmann would sometimes manipulate his music in production to achieve an unusual effect.

The Magnificent Ambersons

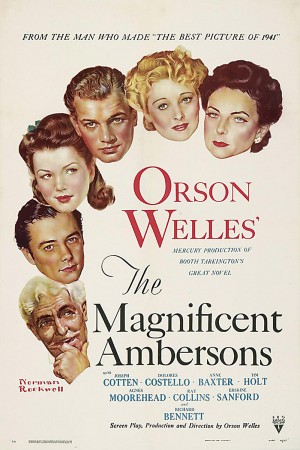

Orson Welles came to Hollywood with a glittering reputation flowing behind him like a sorcerer’s cloak. He cast his spell over RKO president George Schaefer and managed to secure an unprecedented level of control over his first feature. By the time it came to his second picture, Welles’s reputation was beginning to look a little threadbare. Citizen Kane had provoked the wrath of newspaper tycoon W.R. Hearst, who famously tried to have the negatives destroyed and used the not inconsiderable power of his media empire to sabotage the marketing efforts of the studio that had backed the film. Confident in his own ambition, Welles shot his second masterpiece (based on a 1918 novel by Booth Tarkington) and then made the mistake of flying down to Rio to make another picture before delivering a final cut.

Orson Welles came to Hollywood with a glittering reputation flowing behind him like a sorcerer’s cloak. He cast his spell over RKO president George Schaefer and managed to secure an unprecedented level of control over his first feature. By the time it came to his second picture, Welles’s reputation was beginning to look a little threadbare. Citizen Kane had provoked the wrath of newspaper tycoon W.R. Hearst, who famously tried to have the negatives destroyed and used the not inconsiderable power of his media empire to sabotage the marketing efforts of the studio that had backed the film. Confident in his own ambition, Welles shot his second masterpiece (based on a 1918 novel by Booth Tarkington) and then made the mistake of flying down to Rio to make another picture before delivering a final cut.

The 131 minute first cut of The Magnificent Ambersons was poorly received in test screenings and, in Welles’s absence, the studio took the picture away from him, ordered forty minutes to be taken out and called for new scenes to be shot and inserted. Not surprisingly, Herrmann’s music suffered in this process: thirty-one minutes of his fifty-eight minute score were excised, and, to add insult to injury, workmanlike studio composer Roy Webb was drafted in to write new music for the film’s now more uplifting finale. Herrmann asked for his name to be removed from the credits.

The Magnificent Ambersons was finally released in an eighty-eight minute version. Welles dismissed it – “They let the studio janitor cut it in my absence,” was his standard response when asked about it – as he often was – in his late-career persona as chat-show guest extraodinaire. His editing notes for the picture survived, but the film negatives did not (tossed, possibly, like the sled Rosebud, into a studio furnace). Herrmann’s score has been reconstructed and re-recorded. I don’t own the disc myself, so I have been listening to the Welles Raises Kane suite that incorporates some of its themes. It made sense for Herrmann to combine the Kane and Amberson scores into a single suite as both use the waltz form to evoke a sense of loss and nostalgia.

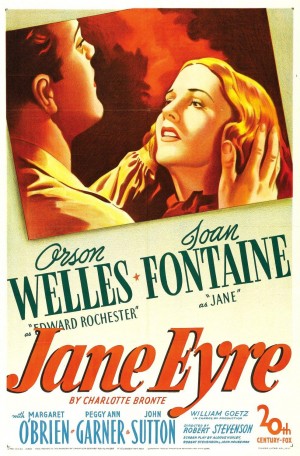

Jane Eyre

Bernard Herrmann was a great Anglophile. He loved English furniture and English antiques, he loved English music and English literature, and toward the end of his life he fell in love with an Englishwoman and married her. He was particularly drawn to the books of the Bronte sisters (he would devote much of his non-film composing energies to writing and trying to stage his opera of Wuthering Heights), and so the opportunity to score a film adaptation of Jane Eyre could not be passed up. Orson Welles, who was signed to play the part of the brooding Mr Rochester in the Twentieth Cenury Fox production, recommended Herrmann to producer Darryl Zanuck, who had been trying unsuccessfully to get Igor Stravinsky to do the score. Herrmann also had a champion in Alfred Newman, a respected film composer himself and head of Fox’s music department, and, despite serious doubts of his own (“There isn’t a chance for me to do the score …” he wrote to his first wife), he got the job. He would later enjoy a long and fruitful relationship with the studio under Newman’s tolerant guidance, and the two men would collaborate on the score to The Egyptian in the 1950s.

Bernard Herrmann was a great Anglophile. He loved English furniture and English antiques, he loved English music and English literature, and toward the end of his life he fell in love with an Englishwoman and married her. He was particularly drawn to the books of the Bronte sisters (he would devote much of his non-film composing energies to writing and trying to stage his opera of Wuthering Heights), and so the opportunity to score a film adaptation of Jane Eyre could not be passed up. Orson Welles, who was signed to play the part of the brooding Mr Rochester in the Twentieth Cenury Fox production, recommended Herrmann to producer Darryl Zanuck, who had been trying unsuccessfully to get Igor Stravinsky to do the score. Herrmann also had a champion in Alfred Newman, a respected film composer himself and head of Fox’s music department, and, despite serious doubts of his own (“There isn’t a chance for me to do the score …” he wrote to his first wife), he got the job. He would later enjoy a long and fruitful relationship with the studio under Newman’s tolerant guidance, and the two men would collaborate on the score to The Egyptian in the 1950s.

The score – which is thundering out of my stereo right now – is a more conventional Hollywood piece, employing a full orchestra and a Wagerian use of leitmotivs (Herrmann, in fact, referred to it as his first “screen opera”). Paul Bowles – known primarily today as the author of The Sheltering Sky , but also an accomplished composer – praised the score for its “Gothic extravagances and poetic morbidities” in an article in the New York Herald Tribune. It’s a phrase that – above any other written about him – captures the essence of Herrmann’s music.

I am listening to a recording of the score conducted by Adriano on the Marco Polo label (Marco Polo 8.223535), a recording which horrified some purists by employing a synthesizer to create the sound of a music box. As I’ve said, I don’t have the musical knowledge to pass judgement on these things. The music is dark and brooding and romantic, and the yearning love theme seems – to my untrained musical ears, at least – to be echoed in the John Williams score for the 1971 Jane Eyre remake.

Hangover Square

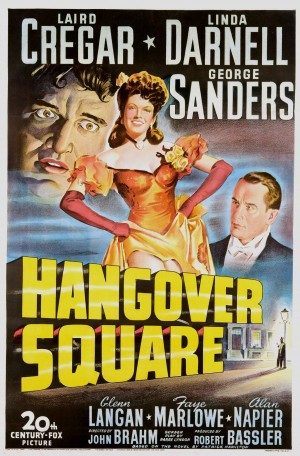

In adapting Patrick Hamilton’s seminal novel of the seedy side of 1930s London life, Hollywood got just about everything wrong. The book’s main character is George Harvey Bone, a schizophrenic who suffers from ‘dead moods’ in which his behaviour becomes unstable and eventually murderous. Hamilton takes us inside his head from the very first word, and manages the difficult feat of making him a sympathetic figure. Bone is smitten with Netta, a failed actress, who – together with her spiv friend Peter – bleeds him dry for money and booze, and manipulates his affections for her own amusement. Despite tantalising suggestions of redemption for the main character, it all ends badly. Bone smashes the back of Peter’s skull with a golf iron, drowns Netta in the bathtub, and then gasses himself in a seaside boarding house.

In adapting Patrick Hamilton’s seminal novel of the seedy side of 1930s London life, Hollywood got just about everything wrong. The book’s main character is George Harvey Bone, a schizophrenic who suffers from ‘dead moods’ in which his behaviour becomes unstable and eventually murderous. Hamilton takes us inside his head from the very first word, and manages the difficult feat of making him a sympathetic figure. Bone is smitten with Netta, a failed actress, who – together with her spiv friend Peter – bleeds him dry for money and booze, and manipulates his affections for her own amusement. Despite tantalising suggestions of redemption for the main character, it all ends badly. Bone smashes the back of Peter’s skull with a golf iron, drowns Netta in the bathtub, and then gasses himself in a seaside boarding house.

Wisely, the film retained the title (which is surely one of the greatest titles ever), but little else. The action was transfered to the turn of the century (possibly because the studio had some available costumes and sets), and Bone becomes a tormented composer-pianist. He strangles rather than drowns Netta, who is a music hall dancer in the movie, and then disposes of her body on a huge Guy Fawkes Night bonfire. Bone is finally consumed by his madness when he gives a performance of his piano concerto in a burning concert hall. As an adaptation of the Hamilton novel, it is a disaster. However, taken on its own terms as a piece of ripe Hollywood melodrama, it’s an enjoyable picture.

The plot, of course, required concert music for the final conflagration, and Herrmann obliged by composing the Concerto Macabre for Piano and Orchestra. It’s a twelve minute stand alone piece that has been recorded several times. The best performance is, I think, by Spanish pianist Joaquín Achúcarro on the RCA disc The Classic Film Scores of Bernard Herrmann. Right now I’m listening to the opening bars as played by Philip Fowke on the Naxos disc Piano Concertos from the Movies (Naxos 8.554323).

In the film, as the fire takes hold of the concert hall, the members of the orchestra desert their instruments whilst Bone plays on like Nero in burning Rome. Herrmann makes the orchestra fall silent for the final twenty eight bars (or two minutes) and allows the maddened pianist to bring the piece to an end with a series of dark chords that suggest a irrevocable descent into madness. The scene – and, in particular, the music – caught the imagination of a fifteen-year-old boy in the audience and he wrote a fan letter to Herrmann. His name was Stephen Sondheim. His own Gothic composition Sweeny Todd, The Demon Barber of Fleet Street owes something to Herrmann’s “poetic morbidities.”

The score for Hangover Square has recently been re-recorded on the Chandos label, but I don’t have this disc. I do have a thirty three minute selection of the original soundtrack on The Marvellous Film World of Bernard Herrmann Volume 2 (Tsunami TCI 0610), but the quality is poor and I don’t listen to it that often. Apart from the concerto, the score has its fair share of violent and dissonant sounds. The piercing piccolo screeches that accompany the murder sequences look forward to the shrieking violins of Psycho, and are about as pleasant to listen to as fingernails scraping down a chalkboard.

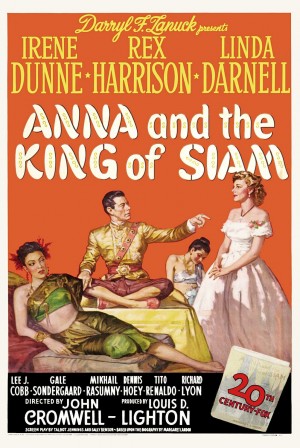

Anna and the King of Siam

Anna and the King of Siam – perhaps better known in its later musical incarnation The King and I – was set in the Orient but filmed on the back lot of Twentieth Century Fox. The picture required music that would give it an Eastern flavour, and Herrmann provided what he somewhat dismissively called “musical scenery”. Just as Max Steiner tried to make the Warner Brothers’ soundstages seem authentically Moroccan with his percussion-tinged score for Casablanca, so Herrmann employed Siamese and Balinese scales and melodies to suggest the exotic locale that the plaster board sets and back projection could not convey on their own.

Anna and the King of Siam – perhaps better known in its later musical incarnation The King and I – was set in the Orient but filmed on the back lot of Twentieth Century Fox. The picture required music that would give it an Eastern flavour, and Herrmann provided what he somewhat dismissively called “musical scenery”. Just as Max Steiner tried to make the Warner Brothers’ soundstages seem authentically Moroccan with his percussion-tinged score for Casablanca, so Herrmann employed Siamese and Balinese scales and melodies to suggest the exotic locale that the plaster board sets and back projection could not convey on their own.

The movie was a box-office and a critical success, and several prominent reviews singled out Herrmann’s contribution. The Academy took note and nominated the score for an Oscar alongside William Walton’s Henry V, Franz Waxman’s Humouresque, Miklos Rozsa’s The Killers, and Hugo Friedhofer’s The Best Years of Our Lives. This last picture – about the difficulties of servicemen returning home after the war – caught the mood of the time, and was the darling of that year’s Oscar ceremony, walking away with seven awards, including one for Friedhofer. Herrmann would not live to see his next two and final Academy Award nominations, which came in the year after his death.

I’m listening to the original soundtrack on the Varese Sarabande label (VSD-6 091) – track 43 (“Montage”) to be precise, which is a typical representative of the Siamese musical scenery. Aside from the travelogue music, there are cues of gloomy brass and woodwind for tension and drama, and some elegiac string writing (a particularly lovely cue called, in fact, “Elegy”). One of my favourite tracks (“3:00 A.M”) is a piece of John Cage-like repetitive piano. As a bonus you also get some outtakes at the end of the disc, including a couple of chants for male voices and four takes on a growling short cue called “Anger” on which you can hear Herrmann’s thick New York accent.

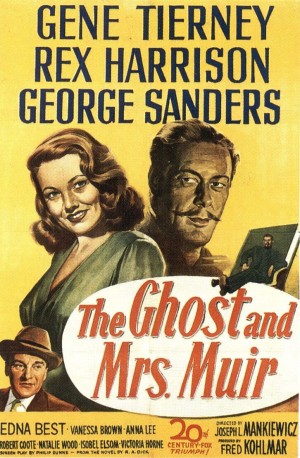

The Ghost and Mrs Muir

Herrmann used to refer to The Ghost and Mrs Muir as his “Max Steiner score”. In saying this he was probably thinking of his extensive use of leitmotivs, associating particular characters with particular melodies and developing them with variations through a movie. This approach was – and still is – standard operating procedure for the film composer: think of James Bond, Indiana Jones or Darth Vader and a theme comes immediately to mind. Max Steiner, who started his Hollywood career a decade before Herrmann, was instrumental in creating the concept of the Hollywood film score and set the bar very high with King Kong (1933).

Herrmann used to refer to The Ghost and Mrs Muir as his “Max Steiner score”. In saying this he was probably thinking of his extensive use of leitmotivs, associating particular characters with particular melodies and developing them with variations through a movie. This approach was – and still is – standard operating procedure for the film composer: think of James Bond, Indiana Jones or Darth Vader and a theme comes immediately to mind. Max Steiner, who started his Hollywood career a decade before Herrmann, was instrumental in creating the concept of the Hollywood film score and set the bar very high with King Kong (1933).

In truth, Herrmann had already written a score that lent heavily on the leitmotiv in Jane Eyre. The music for that film, however, had enough growling brass and unsettling woodwinds to mark it out as “a Herrmann score”. The Ghost and Mrs Muir – the story of a relationship between a young English widow called Lucy Muir and the spirit of a sea captain – is an altogether more tender affair, and it brought out in the composer a romantic sense of longing. True, there are some cues with a hint of menace – I’m listening to one right now called, perhaps appropriately, “The In-Laws” – and some that are tinged with an eerie quality, but the overall tone of the score is wistfully romantic. Even the titles of the cues (“Farewell”, “Sorrow”, “The Empty Room”, “The Passing Years”) convey a mood of loss and longing. Of them all, the most beautiful cue is “Andante Cantabile”. In the movie this piece underscores Lucy’s reminiscences of the captain and is an example of how effectively Herrmann could write under dialogue. The composer also writes a dramatic rising motif for the sea and employs a lyrical melody that he will rework in a later maritime score Beneath the Twelve Mile Reef.

I’m playing the Varese Sarabande disc (VSD-5850), which is from the original soundtrack. The score was also recorded by Elmer Bernstein in 1985, but I’ve not heard it. For my money, the Joel McNeely version of the “Andante Cantabile” – the single cue from the film that appears on the Farenheit 451 compilation disc (VSD-5551) – is the most achingly beautiful three minutes and thirty three seconds of Herrmann in my entire collection.

![The Man Who Knew Too Much – 4K restoration / Blu-ray [A]](http://www.bernardherrmann.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/TMWKTM-4K.jpeg)

![The Bride Wore Black / Blu-ray [B]](http://www.bernardherrmann.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/07/BrideWoreBlack.jpeg)

![Alfred Hitchcock Classics Collection / Blu-ray [A,B]](http://www.bernardherrmann.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/AHClassics1.jpg)

![Endless Night (US Blu-ray) / Blu-ray [A]](http://www.bernardherrmann.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/EndlessNightUS.jpg)

![Endless Night (UK Blu-ray) / Blu-ray [B]](http://www.bernardherrmann.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/12/ENightBluRay.jpg)