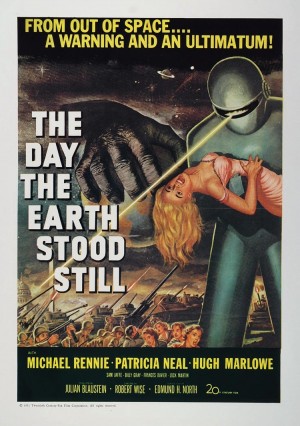

The Day the Earth Stood Still

The wailing theremin from The Day the Earth Stood Still – cliche though it may have now become – is the sound of Fifties science fiction. The whole score, which runs to just over thirty minutes on disc, is shot through with weird and wonderful sounds. As well as two high and low electric theremins, Herrmann employs an electric violin and electric bass to supplement an already eccentric ensemble of four pianos, four harps and an eclectic collection of 30-odd brass players.He also fiddled with the engineering and production of the sounds this unusual combo produced, playing some parts backwards and overlaying sections with oscillator test signals. The result is a score that combines quiet beauty (“Solar Diamonds”) with cacophonous terror (“Gort” or “Magnetic Pull”).

The wailing theremin from The Day the Earth Stood Still – cliche though it may have now become – is the sound of Fifties science fiction. The whole score, which runs to just over thirty minutes on disc, is shot through with weird and wonderful sounds. As well as two high and low electric theremins, Herrmann employs an electric violin and electric bass to supplement an already eccentric ensemble of four pianos, four harps and an eclectic collection of 30-odd brass players.He also fiddled with the engineering and production of the sounds this unusual combo produced, playing some parts backwards and overlaying sections with oscillator test signals. The result is a score that combines quiet beauty (“Solar Diamonds”) with cacophonous terror (“Gort” or “Magnetic Pull”).

Since it first appeared in 1951 Herrmann’s score has been imitated and parodied to death. Danny Elfman used it as a template for Mars Attacks!, which itself was a parody of the Fifties alien invasion genre. When The Day the Earth Stood Still was remade in 2008 there was anticipation among Herrmann die-hards that his score might be reused (as had happened previously on the Psycho and Cape Fear remakes), but it was not to be. I saw the movie, but don’t remember the music so can only assume that it was as bland as Keanu Reeves’ performance.

Herrmann’s original score was released on the now discontinued Fox Classics series (07822-11010-2) in 1993 with a cool image of Gort’s visored head on the CD itself, and this is the version I’m listening to now (the spooky Track 16 “Departure” about to segue into the plaintive Track 17 “Farewell”). It has also been more recently recorded by Joel McNeely.

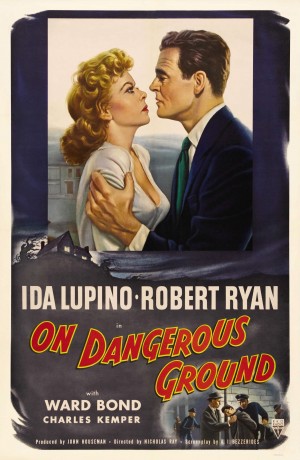

On Dangerous Ground

On Dangerous Ground was the second release of 1951 to have a Herrmann score although the composer had started work on the picture in November of the year before. In fact, he completed the composition at a quarter to five in the afternoon on New Year’s Eve. The film is a gritty crime drama that starts out in a familiarly bleak urban environment and then moves to a less familiar but equally bleak rural landscape. Bad cop Jim Wilson is transferred upstate to investigate a murder and becomes involved with the blind sister of the suspect he is pursuing. The storyline gave Herrmann the opportunity to write some blistering chase music (“The Death Hunt”), some churning string patterns (“Snowstorm”) that crop up again in his later Hitchcock scores, and a tender love theme (“Blindness”) written specifically for the viola d’amore.

On Dangerous Ground was the second release of 1951 to have a Herrmann score although the composer had started work on the picture in November of the year before. In fact, he completed the composition at a quarter to five in the afternoon on New Year’s Eve. The film is a gritty crime drama that starts out in a familiarly bleak urban environment and then moves to a less familiar but equally bleak rural landscape. Bad cop Jim Wilson is transferred upstate to investigate a murder and becomes involved with the blind sister of the suspect he is pursuing. The storyline gave Herrmann the opportunity to write some blistering chase music (“The Death Hunt”), some churning string patterns (“Snowstorm”) that crop up again in his later Hitchcock scores, and a tender love theme (“Blindness”) written specifically for the viola d’amore.

The recording I’m listening to is the FSM disc in the Turner Classic Movies series (FSM Vol 6 no. 18) and consists of the original score taken from acetate playback discs. The CD comes with a warning that “surface noise is inherent in the transfers, and is especially noticeable in [some] cues.” They’re not kidding. The one I’m listening to right now (Cue19 “The Parting/The Return/The City/Finale”) is popping and hissing like an old well-worn piece of vinyl. But – to paraphrase British DJ John Peel – I rather like surface noise.

Having said that, I do prefer the Charles Gerhardt interpretation of “The Death Hunt” cue on RCA disc The Classic Film Scores of Bernard Herrmann. If there was one single piece of music that made me a Herrmann fan, it was that scorching performance, with its eight horns baying like the hounds of hell and a viciously struck steel plate that initially made me think the needle of my record player had skipped a groove. Herrmann was rightly proud of the piece (he, in fact, suggested its inclusion on the RCA disc), and it works as a rousing encore in the concert hall. You can see the Los Angeles Philharmonic performing it here.

Despite its surface noise problems – or, indeed, maybe because of them – the FSM disc is one of my favourite Herrmann recordings. As a bonus there are some outtakes at the end where you get to hear Herrmann berating the horn players and waxing lyrical over the viola d’amore.

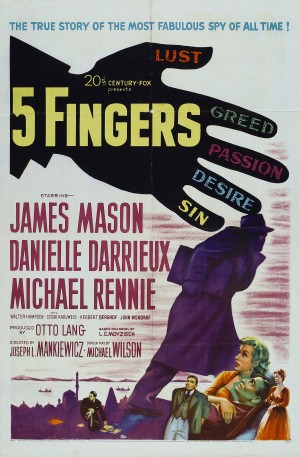

Five Fingers

“REAL AS THE STREETS OF ANKARA AND ISTANBUL – WHERE IT ALL HAPPENED! TRUE AS THE INTRIGUES OF A MASTER SPY – GUILTY OF EVERY SIN THAT HAD A NAME!” Thus screamed the movie poster tag lines for Five Fingers, an espionage drama set in wartime Turkey. The five fingers of the title – as the poster tried to explain – were those of an amoral spy codenamed Cicero, who was intent on selling the secrets of the Normandy invasion plans to the highest bidder. Although filmed mostly on the Fox backlot, director Joseph Mankiewicz took a camera crew to Istanbul to shoot background footage.

“REAL AS THE STREETS OF ANKARA AND ISTANBUL – WHERE IT ALL HAPPENED! TRUE AS THE INTRIGUES OF A MASTER SPY – GUILTY OF EVERY SIN THAT HAD A NAME!” Thus screamed the movie poster tag lines for Five Fingers, an espionage drama set in wartime Turkey. The five fingers of the title – as the poster tried to explain – were those of an amoral spy codenamed Cicero, who was intent on selling the secrets of the Normandy invasion plans to the highest bidder. Although filmed mostly on the Fox backlot, director Joseph Mankiewicz took a camera crew to Istanbul to shoot background footage.

Herrmann did not feel obliged -as he had on Anna and the King of Siam – to provide “musical scenery” this time and included only one cue (“The Old Street”) which had a Turkish flavour to it. Not wanting to squander his talents he went on to recycle this cue for The Seventh Voyage of Sinbad, and other suspense cues from the score found themselves being pressed into service again in Psycho and in Vertigo. Self-borrowing is not plagiarism and is common among artists. For Herrmann, though, it was a sensitive topic. When in a 1971 interview writers Greg Rose and Leslie Zador alluded to this musical cross-pollenation in his work, Herrmann went ballistic. “THAT’S BECAUSE IT HAPPENS TO BE ME! I WAS THE COMPOSER OF BOTH! I SOUND LIKE MYSELF!”

Hitchcock also drew Herrmann’s attention to the similarity between the scores of Marnie and Joy in the Morning. In a lengthy cable to the composer he wrote: I WAS EXTREMELY DISAPPOINTED WHEN I HEARD THE SCORE OF JOY IN THE MORNING, NOT ONLY DID I FIND IT CONFORMING TO THE OLD PATTERN BUT EXTREMELY REMINISCENT OF THE MARNIE MUSIC. IN FACT, THE THEME WAS ALMOST THE SAME. (Hitchcock wasn’t shouting – it’s just that cables were always written out in capitals). Actually, this was a case of the pot calling the kettle black as Hitchcock had ripped himself off in Marnie, stealing the famous sweeping crane shot from Notorious for the scene where Strutt arrives at the Rutland party. Still, there was no arguing with Hitchcock. And there was always arguing with Herrmann. Not surprisingly, their working relationship did not last much longer.

The recording of Five Fingers I’ve been listening to while typing the above is on the Marco Polo label twinned with The Snows of Kilimanjaro (8.225168). Though it’s one of Herrmann’s lesser known scores, I find myself playing it quite regularly, and I think “The Pursuit” cue can rival any of John Powell’s Bourne scores for tension and excitement. The score was restored by John Morgan and conducted by William Stromberg, two men who have served Herrmann’s legacy well.

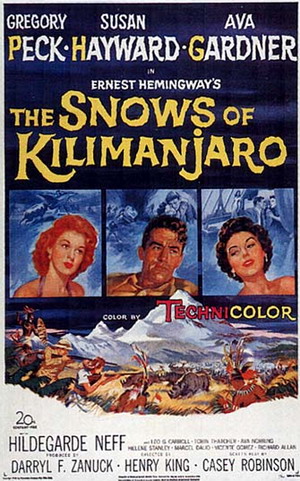

The Snows of Kilimanjaro

Like Hangover Square, The Snows of Kilimanjaro was another case of Hollywood taking a classic work of modern literature and adapting it beyond all recognition. Hemingway hated the end result – particularly the changed ending – and referred to it dismissively as the “Snows of Zanuck” after the film’s producer. Although it boasts impressive set design and atmospheric lighting, it suffers -at least in retrospect – from obvious back projection. Gregory Peck and Susan Hayward on a lake full of hippos are clearly in a studio tank acting against a screen. What the film does have going for it is a magnificent score by Herrmann.

Like Hangover Square, The Snows of Kilimanjaro was another case of Hollywood taking a classic work of modern literature and adapting it beyond all recognition. Hemingway hated the end result – particularly the changed ending – and referred to it dismissively as the “Snows of Zanuck” after the film’s producer. Although it boasts impressive set design and atmospheric lighting, it suffers -at least in retrospect – from obvious back projection. Gregory Peck and Susan Hayward on a lake full of hippos are clearly in a studio tank acting against a screen. What the film does have going for it is a magnificent score by Herrmann.

Although Herrmann did not hold Hemingway in very high regard as a writer (“a complete piece of corn” is how he descibed him), he was keen to work on a project that would allow him a more colourful orchestral palate. He was also drawn to the elements of nostalgia inherent in the story of a disillusioned writer looking back on his life as he faces death on an African safari. The most perfect expression of these Proustian-like reflections is to be found in the cue “Memory Waltz”, a delicate valse triste (or sad waltz) that aches with a longing for the memory of things past. Herrmann himself liked the piece so much that he included it on one his Decca London recordings alongside his more well known scores.

There are moments of terror in the score (from the slouching, prowling piece called “The Hyena” to the heart-stopping opening of the “Witch Doctor” cue), but it is the sad and haunting melodies that linger. The score is available on the Marco Polo label (8.225168) alongside Five Fingers.

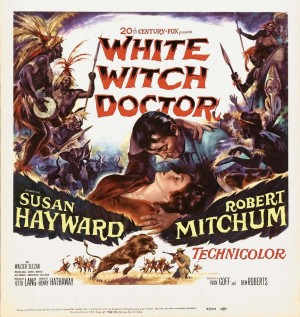

White Witch Doctor

After The Snows of Kilimanjaro, Herrmann stayed (musically, not literally) in Africa for his next assignment, White Witch Doctor. Although it was not as prestigious a production as the Zanuck picture, it was a well-crafted entertainment that boasted an appealing cast and some colourful location work. Robert Mitchum was his normal stoical self in the role of Lonni Douglas, animal wrangler and fortune hunter, who is hired to take Nurse Ellen Burton (Susan Hayward) upriver to help bring the white man’s modern medicines to the indigenous population. On the way they encounter the kind of dangers you would expect (gorillas, lions, hostile natives, and large spiders) and – also as you would expect – they begin to fall in love.

After The Snows of Kilimanjaro, Herrmann stayed (musically, not literally) in Africa for his next assignment, White Witch Doctor. Although it was not as prestigious a production as the Zanuck picture, it was a well-crafted entertainment that boasted an appealing cast and some colourful location work. Robert Mitchum was his normal stoical self in the role of Lonni Douglas, animal wrangler and fortune hunter, who is hired to take Nurse Ellen Burton (Susan Hayward) upriver to help bring the white man’s modern medicines to the indigenous population. On the way they encounter the kind of dangers you would expect (gorillas, lions, hostile natives, and large spiders) and – also as you would expect – they begin to fall in love.

Although White Witch Doctor was nothing more than a well polished B picture, Herrmann brought his A game to it, and produced one of his most exotic and colourful scores. Having avoided the obvious cliches of scoring an African-set picture in Kilimanjaro, Herrmann now embraced the opportunity to weave the rhythms of the jungle into his music. The main title sequence was scored with a savage and pulsating dance for full orchestra with an augmented percussion section (including a native log drum, a brake drum, marimbas, and maracas). Herrmann provides evocative “musical scenery” for “The Safari”, using individual instruments to suggest the sounds of the jungle. For a sequence in which a sleeping Susan Hayward is menaced by a large spider, the composer employed a bass wind instrument called a serpent. The sound it produced – a slow poisonous growl – was the perfect accompaniment for a creeping arachnid. For the romance between the adventurer and the nurse, Herrmann wrote a beautiful “Nocturne” for strings and solo clarinet, and, as was his custom with his best tunes, he recyled it as the love theme for North by Northwest.

Both Alfred Newman and Darryl Zanuck enthused about the score. “One of the very best we have on any of our pictures,” gushed the head of the music department. The head of the stuido concurred. “In every respect this is a wonderful score,” he wrote in a memo to the film’s producer. “It has great class and distinction.” All this love for the score most likely secured Herrmann his next gig – Beneath the Twelve Mile Reef - which would also require musical colour to give it a lift.

Given the praise that has been heaped on White Witch Doctor, it’s curious that it is one of the few remaining Herrmann scores that has not been released on CD or re-recorded. There’s a suite on the RCA disc The Classic Film Scores of Bernard Herrmann and, at just under fourteen minutes, it’s a tantalising appetiser, but not satisfying enough. What is doubly frustrating is that my cassette tape transfer of the original vinyl – currently in storage – cuts out about three and a half minutes before the end.

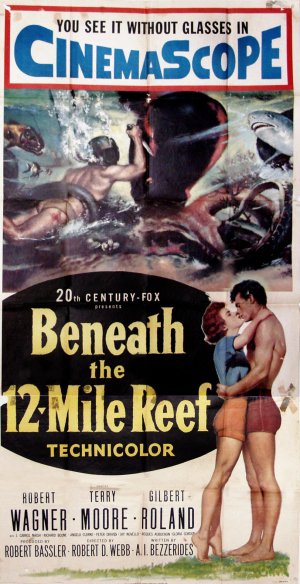

Beneath the Twelve Mile Reef

In an attempt to draw audiences away from their televisions and back into the cinemas, Fox started to film and present its movies in widescreen and stereophonic CinemaScope from 1953. Beneath the Twelve Mile Reef was the first film in this format that Herrmann scored and he responded to its sumptuous photography and visual scale with one of his greatest scores. Unfortunately, its story of two rival families of sponge fishermen off the Florida coast was not equal to the size of the picture, and the young leads Robert Wagner and Terry Moore lacked chemistry. Although the Romeo and Juliet underwater plotline failed to excite Herrmann, there were plenty of visuals above and below the waves that provided him with rich possibilities for inventive scoring.

In an attempt to draw audiences away from their televisions and back into the cinemas, Fox started to film and present its movies in widescreen and stereophonic CinemaScope from 1953. Beneath the Twelve Mile Reef was the first film in this format that Herrmann scored and he responded to its sumptuous photography and visual scale with one of his greatest scores. Unfortunately, its story of two rival families of sponge fishermen off the Florida coast was not equal to the size of the picture, and the young leads Robert Wagner and Terry Moore lacked chemistry. Although the Romeo and Juliet underwater plotline failed to excite Herrmann, there were plenty of visuals above and below the waves that provided him with rich possibilities for inventive scoring.

To depict the sea he used harps and horns over a broad string melody and its presentation over the main titles gives a promise of adventure and romance that the picture is unfortunately unable to deliver. With each harp player (and there were nine of them) playing a separate glissando, the music crashes around your ears like waves. When above the water, the music is jaunty and almost playful (rather like the piratical music that John Williams provided for Jaws), but below the surface it becomes dark and sinister. Herrmann marks the divers’ descent underwater with harp arpeggios and as they go deeper he uses brass and organ to suggest the mounting pressure and the shifting currents. Some of these same techniques would be put to similar effect in the subterranean world of Journey to the Centre of the Earth and in the underwater sequences in Mysterious Island.

Darryl Zanuck was suitably impressed and shot off a memo to head of music Alfred Newman. “I thought Beneath the Twelve Mile Reef one of the most original scores I have ever heard. It really gave me a thrill … The entire picture has been enormously enhanced … [The music] gives it a bigness it did not originally have.”

Herrmann paid almost as much attention to the recording of the score as he did to the writing of it. Unusually for a composer, he was allowed to conduct his own work at Fox, and he was nearly obsessive about the placing of microphones to take advantage of the extended dynamic range offered by CinemaScope. The nine harps were also positioned strategically around the orchestra to allow for a wide as possible range of sound.

The full score is available on an FSM release (FSM Vol. 3 No.10), but has deteriorated over the years. There are several significant moments of distortion and drop-out, but this is a small price to pay for being able to hear the complete score. Prior to this release, only a twelve minute suite had been available on the RCA disc. Wonderfully recorded by the National Philharmonic Orchestra under Charles Gerhardt, the suite is a glorious glowing tone poem to the sea.

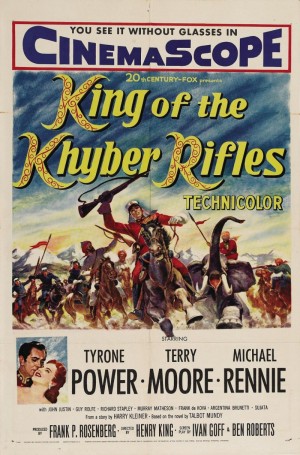

King of the Khyber Rifles

King of the Khyber Rifles was a tale of military derring-do with a Kiplingesque setting. Based on a jingoistic novel by Talbot Mundy, the movie was actually a remake, having previously been filmed under the title The Black Watch in 1929. It starred Tyrone Power (in the twilight of his career) and a sour-faced Terry Moore, who had provided the love interest in Beneath the Twelve Mile Reef. Despite the studio’s attempts to market the film as an epic adventure, it was greeted with indifference by the public and was one of Fox’s least successful releases of the year.

King of the Khyber Rifles was a tale of military derring-do with a Kiplingesque setting. Based on a jingoistic novel by Talbot Mundy, the movie was actually a remake, having previously been filmed under the title The Black Watch in 1929. It starred Tyrone Power (in the twilight of his career) and a sour-faced Terry Moore, who had provided the love interest in Beneath the Twelve Mile Reef. Despite the studio’s attempts to market the film as an epic adventure, it was greeted with indifference by the public and was one of Fox’s least successful releases of the year.

The film’s director was Henry King, who had made The Snows of Kilimanjaro, and when original choice of composer Hugo Friedhofer withdrew from the project, Herrmann seemed like an obvious replacement. Looking back on the assignment in 1961, the composer remarked that “Everybody’s life has some rain in it.” The score he produced was a serviceable accompaniment to the onscreen action. There’s a military march for the British soldiers on horseback, some strident brass and cymbal crashes for a violent windstorm and a love theme for the lovers. For a sequence entitled “Attack on the Mountain Stronghold” Herrmann provides a magnificent set piece of pounding percussion, which may well have influenced Jerry Goldsmith’s score for The Wind and the Lion.

Herrmann’s score is not well represented on disc. There are six cues on Bernard Herrmann At Fox Volume 2 (VSD-6053), and three minutes and eleven seconds of those pounding drums on The Spectacular World of Classic Film Scores (RL 42005) – a smorgasbord of the best of the RCA discs with some additional unreleased pieces. It’s not a score that I listen to much, but perhaps a full re-recording would change my mind.

Garden of Evil

In the Fifties Max Steiner and Dimitri Tiomkin were the usual go-to guys for Westerns, but Bernard Herrmann managed to get in on the act in 1954 with his score for Henry Hathaway’s Garden of Evil. Although the composer would go on to write music for the television shows Gunsmoke and The Virginian and provide a score to Burt Lancaster’s The Kentuckian, it is not a genre that many people associate him with.

In the Fifties Max Steiner and Dimitri Tiomkin were the usual go-to guys for Westerns, but Bernard Herrmann managed to get in on the act in 1954 with his score for Henry Hathaway’s Garden of Evil. Although the composer would go on to write music for the television shows Gunsmoke and The Virginian and provide a score to Burt Lancaster’s The Kentuckian, it is not a genre that many people associate him with.

Garden of Evil is essentially a Western variation on The Treasure of the Sierra Madre, which is itself a kind of neo-Western. The picture starred Cary Cooper, fresh from his Oscar-winning role in High Noon as the town marshal standing up against impossible odds. Susan Hayward appeared in her third Herrmann-scored movie as the woman who hires Cooper and his fellow prospectors to rescue her husband from hostile Indian territory. Another Western stalwart Richard Widmark was along for the ride.

The movie was filmed on location in southern Mexico and made good use of the rugged terrain, and Herrmann responded with some equally rugged music. Mining themes he had used for his First Symphony (written in 1941 around the time of Citizen Kane), he provided a loud and brash score with the blaring horns and strident timpani that were becoming his stock in trade. The score does have its quieter moments: a lilting cantina song (“Me-Mue”), softly crooned on the soundtrack by Rita Moreno, and a playful Appalacian-tinged piece called “The Wild Party”, which anticipates the idiom of Herrmann’s later score for The Kentuckian. The overall impression, however, is one of doom and gloom, and for some Herrmann laid it on a bit too thick. A reviewer in Variety objected to the “misuse of [...] the background score” and went on to say that “the music is permitted to become so busy that it is impossible to concentrate on the drama.”

The original soundtrack is available on Bernard Herrmann at Fox Vol 2 (VSD.6053), which I’ve been listening to while writing this. A re-recording of the complete score is also available on the Marco Polo label (8. 223841). I’ve not heard this version but, given that it comes from John Morgan and William Stromberg, I’d bet my last plugged nickel that it’s a sublime recording.

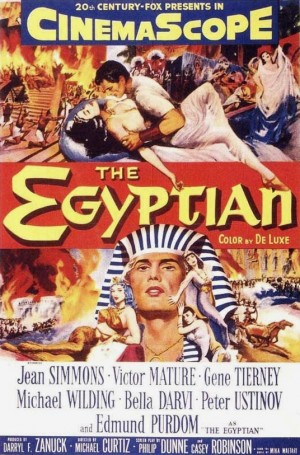

The Egyptian

The music score to The Egyptian is credited to two composers: Alfred Newman and Bernard Herrmann. Although it’s true that Herrmann shared credit with other composers on movies that required songs – most famously Jay Livingston and Ray Evans, who provided “Que Sera Sera” for The Man Who Knew Too Much – and was credited as “a sound consultant” alongside Oskar Sala and Remi Gassmann for the non-musical sountrack for The Birds, The Egyptian remains the only true collaboration of his film scoring career.

The music score to The Egyptian is credited to two composers: Alfred Newman and Bernard Herrmann. Although it’s true that Herrmann shared credit with other composers on movies that required songs – most famously Jay Livingston and Ray Evans, who provided “Que Sera Sera” for The Man Who Knew Too Much – and was credited as “a sound consultant” alongside Oskar Sala and Remi Gassmann for the non-musical sountrack for The Birds, The Egyptian remains the only true collaboration of his film scoring career.

The decision to use two composers on one film was a pragmatic rather than an artistic one. Studio head Darryl Zanuck was personally invested in the production and wanted his head of music Alfred Newman to do the score. Though he was keen to do it, Newman’s other commitments would not allow him to commit fully to the project, and so Herrmann was brought on board. The two men did not actually sit down in a room and write music together (in fact, they consulted only twice during the scoring process), but carved the film up and worked independently. Newman scored the mystical sequences (“Valley of the Kings, “Death of Akhnaton”) and drew on his reserves of ethereal string writing that had served him well on religious-themed pictures such as The Song of Bernadette and The Robe. Unsurprisingly, Herrmann opted to score the darker elements of the film (“Violence”, “The Holy War”, “Dance Macabre”) and added a chorus to the orchestra to give it an element of spiritual mystery.

Despite the circumstances of its production, the score emerged as a coherent and genuinely affecting piece of music. Herrmann was not an easy man to work with, and it’s testament to his relationship with Newman that this project went so smoothly. Those familiar with the work of both composers will have no trouble identifying who wrote what (more than half of the score was composed by Herrmann). For the uninitiated the Marco Polo re-recording by Morgan and Stromberg (8.225078) helpfully provides an asterisk against the tracks written by Alfred Newman.

The film itself turned out to be a disaster – mostly due to bad decisions by producer Zanuck – but the album of the soundtrack was a hit.

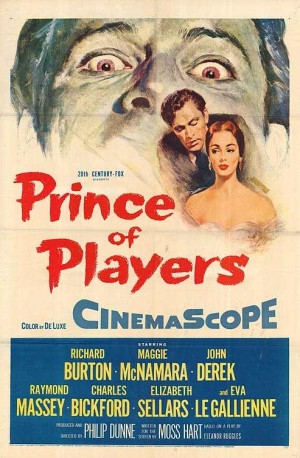

Prince of Players

Prince of Players, the true life story of a theatrical family, was the directorial debut of respected Hollywood screenwriter Philip Dunne, whose work included the script for The Ghost and Mrs Muir. Dunne, who asked for Herrmann to score his picture, was himself knowledgeable about music and was able to give his composer notes on orchestration – notes which Herrmann rejected out of hand, saying, “Well, if you know so much about it, why don’t you write the music?” Despite these occasional run-ins the collaboration was a fruitful one.

Prince of Players, the true life story of a theatrical family, was the directorial debut of respected Hollywood screenwriter Philip Dunne, whose work included the script for The Ghost and Mrs Muir. Dunne, who asked for Herrmann to score his picture, was himself knowledgeable about music and was able to give his composer notes on orchestration – notes which Herrmann rejected out of hand, saying, “Well, if you know so much about it, why don’t you write the music?” Despite these occasional run-ins the collaboration was a fruitful one.

Two years earlier Herrmann had narrowly lost out to Miklos Rozsa on scoring MGM’s prestigious production of Julius Caesar, starring Marlon Brando and John Gielgud. Prince of Players, which interpolates scenes from Hamlet, King Lear and The Tempest within its own family drama, now gave Herrmann to opportunity to write for Shakespeare. In fact, much of the music in the film is heard under dialogue and Herrmann proved once again that he was a master of the technique. The “Prelude”, which opens the film, is a theatrical curtain-raiser to the drama, an extended fanfare that suggests the pageantry of the theatre and would not have been out of place as the title music for a knights in armour spectacle.

The score is represented on two discs. There are seven cues from the original soundtrack on Bernard Herrmann at Fox Volume 2 (VSD-6053), and eight cues of re-recorded music on the Morgan/Stromberg disc (8.223841).

The film was liked by the critics, but the public stayed away in droves, and Dunne proudly claimed in his autobiography that the picture had “the dubious distinction of becoming the first production in CineamScope to lose money.” Dunne wanted Herrmann to score his second picture – The View from Pompey’s Head – but the composer had to decline the offer, having received a call from Alfred Hitchcock. Herrmann was about to embark on the most productive and most turbulent professional relationship of his career.

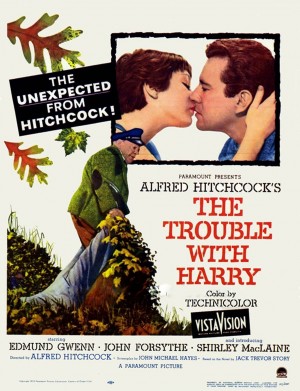

The Trouble With Harry

In the history of film and of film music the names of Bernard Herrmann and Alfred Hitchcock are inextricably bound together. Their eleven years of collaboration happily occured when both artists were at the height of their powers and it produced an unprecedented run of masterpieces from Vertigo to Marnie (yes, I’m one of those people who think Marnie is a masterpiece).

In the history of film and of film music the names of Bernard Herrmann and Alfred Hitchcock are inextricably bound together. Their eleven years of collaboration happily occured when both artists were at the height of their powers and it produced an unprecedented run of masterpieces from Vertigo to Marnie (yes, I’m one of those people who think Marnie is a masterpiece).

It all started with The Trouble with Harry, a whimsically macabre comedy of a body that refuses to stay buried. It’s not laugh-out-loud funny like Some Like It Hot and it probably has fewer jokes than North by Northwest, but the story appealed to Hitchcock’s droll sense of humour. By the mid Fifties (with Dial M for Murder, Rear Window and To Catch a Thief under his belt) Hitchcock could have convinced any studio to let him film the telephone book.

Hitchcock had already worked with a number of top rank Hollywood composers (Franz Waxman on Rebecca, Suspicion, The Paradine Case and Rear Window, Miklos Rozsa on Spellbound, Dimitri Tiomkin on Strangers on a Train and Dial M for Murder), but – with the possible exception of Spellbound - none of them had produced any stand-out musical moments. Hitchcock was quick to realise that by giving Herrmann free rein he could dispense with dialogue and exposition and tell the story purely through visual and aural means.

On their first feature, however, the music played an incidental role. The opening credit sequence – drawn by artist Saul Steinberg – establishes the mood along with Herrmann’s impish music. In tone it is not dissimilar to his arrangement of Gounod’s Funeral March of a Marionette that was to become Hitchock’s signature tune. Indeed, when Herrmann arranged and recorded a suite of the music from The Trouble with Harry in the Sixties, he titled it “A Portrait of Hitch”. At that time he described the music as “gay, macabre, tender, and with an abundance of [...] sardonic wit” – a description that would fit the film’s director equally well.

Unencumbered by the dark obsessions of Hitchcock’s later work, The Trouble with Harry gave Herrmann the opportunity to show his lighter side. The jaunty rhythms of his score accompany the characters as they crisscross the autumnal New England countryside, and, though there are some sombre tones woven into the musical patterns, there is more light than shade in the score.

For years the music was only available in the suite that Herrmann arranged for his Decca album The Great Hitchcock Movie Thrillers (B000004261). In the Nineties Varese Sarabande produced a series of Hitchcock/Herrmann scores conducted by Joel McNeely, and The Trouble with Harry was one of them (VSD-5971).

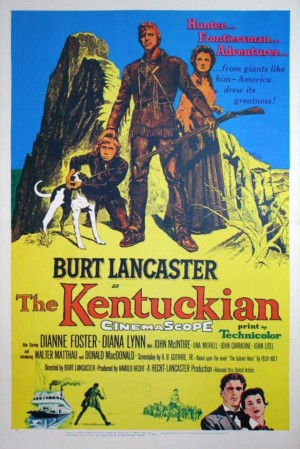

The Kentuckian

Herrmann’s score for his second Western differed quite substantially from the one he provided for his first. Whereas the music for Garden of Evil was harsh and unforgiving, The Kentuckian was warm and lyrical. In a sense the scores reflect the movies’ two different landscapes: one, the dry desert and rock of Michoacan in southern Mexico; the other, the green wilderness of Kentucky. For Burt Lancaster’s first picture as director Herrmann chose a recognisably American idiom to write in, one that is reminiscent of Aaron Copland’s Rodeo music. Some of the cues (“The Stagecoach”, “The Steamboat”, “Welcome Aboard” and “Scherzo”) have a toe-tapping barn dance energy to them that makes you want to throw a Stetson into the air and shout “Yeehaw!”

Herrmann’s score for his second Western differed quite substantially from the one he provided for his first. Whereas the music for Garden of Evil was harsh and unforgiving, The Kentuckian was warm and lyrical. In a sense the scores reflect the movies’ two different landscapes: one, the dry desert and rock of Michoacan in southern Mexico; the other, the green wilderness of Kentucky. For Burt Lancaster’s first picture as director Herrmann chose a recognisably American idiom to write in, one that is reminiscent of Aaron Copland’s Rodeo music. Some of the cues (“The Stagecoach”, “The Steamboat”, “Welcome Aboard” and “Scherzo”) have a toe-tapping barn dance energy to them that makes you want to throw a Stetson into the air and shout “Yeehaw!”

For many years all I had of the music was on a Preamble disc (PRCD 1777). The CD was called The Kentuckian, but it had only nineteen minutes of the score arranged in a symphonic suite that favoured the Coplandesque cues. The full score was re-recorded by Morgan/Stromberg in 2007 on their new Tribute Film Classic label (TFC-1004), and it revealed that the do-si-do hoedown numbers – pleasing though they are – are just a small part of the overall work. There are moments of nerve-shredding tension (“The Rope”, “The Kill”) and brooding suspense (“Anger”), and shimmering string interludes (“Nocturne”). Sometimes single tracks manage to encompass all three (“The Boy and his Dog”). There’s even some authetic bar room source music (“Saloon Piano”, “The Gamblers”). The forty eight cues (some as short as seventeen seconds) are woven together to form a rich quilt of Americana.

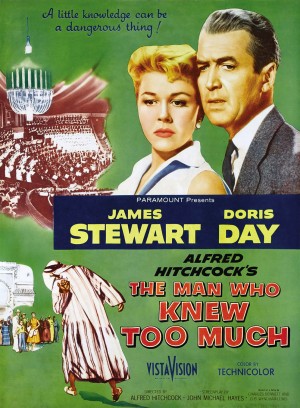

The Man Who Knew Too Much

The Man Who Knew Too Much, the second Hitchcock film to have a Herrmann score, found the director on familiar ground. Very familiar, in fact – he had made the picture once before in the Thirties. Hitchcock had been toying with the idea of an American remake for some time (he had pitched the idea to his first Hollywood producer David O. Selznick in 1940), and now, supremely confident in what would be his best decade, he returned to the concept. The basic story – a family become unwittingly embroiled in an international assassination plot – remained the same, as did the picture’s climactic scene that takes place during a concert at London’s Royal Albert Hall.

The Man Who Knew Too Much, the second Hitchcock film to have a Herrmann score, found the director on familiar ground. Very familiar, in fact – he had made the picture once before in the Thirties. Hitchcock had been toying with the idea of an American remake for some time (he had pitched the idea to his first Hollywood producer David O. Selznick in 1940), and now, supremely confident in what would be his best decade, he returned to the concept. The basic story – a family become unwittingly embroiled in an international assassination plot – remained the same, as did the picture’s climactic scene that takes place during a concert at London’s Royal Albert Hall.

With a much bigger budget the second time around Hitchcock elected to shoot on location (in Morocco and England) and brought Herrmann along. The composer’s duties on the picture were not limited to writing the score: he played himself – spiffly turned out in white tie and tails – in the Albert Hall sequence, and Hitchcock gave him an extra credit by including a brief shot of his name on a poster as Doris Day runs into the building. The music Herrmann conducted for the big scene was not his own, but a somberly serious piece called “The Storm Clouds Cantata” by Australian composer Arthur Benjamin. It had been composed specifically for the original movie and, although Herrmann was given the opportunity to write a new cantata of his own, he chose to adapt Benjamin’s original piece. During breaks in the filming at the Albert Hall Herrmann regaled the orchestra with Hollywood gossip and impressed them with his encyclopaedic knowledge of music. As a parting gift the musicians gave the composer a book inscribed “To Bernard Herrmann, the Man Who Knows So Much”.

In fact, there is very little original Herrmann music in the film. He wrote a striking prelude for the opening titles, a thrilling percussion sequence for the chase through the market place in Marrakech, some standard moody bass clarinet for suspense, and a brief comedic piece for the struggle in a London taxidermist’s shop. All together it was the least amount of music he had written for any film. This explains why the full score has never surfaced on disc. The Prelude was recorded by the Los Angeles Philharmonic for the Sony Film Scores CD (SK 62700) and the Benjamin Cantata is a curious inclusion on Elmer Bernstein’s Bernard Herrmann Film Score Tribute (Milan 71000-2).

In fact, the most recorded piece of music from the film was not by Herrmann, but by the songwriting duo Jay Livingston and Ray Evans. Although it was not written to order for the film, “Whatever Will be, Will Be (Que Sera Sera)” won the Oscar for Best Song in 1956 and quickly became a popular standard. Surprisingly, given his later antipathy to the practice of shoe-horning songs into movies to sell records, Herrmann defended its inclusion in the picture. “It was not a predmeditated attempt at song-plugging,” he said. “All pop hits are accidental. Like gold, it’s where you find it.”

The Man in the Gray Flannel Suit

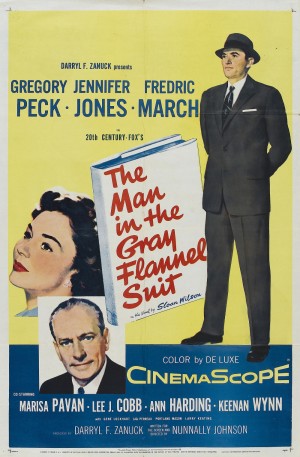

Although the title of Herrmann’s second film of 1956 had an echo of the Hitchcock thriller he had just completed, The Man in the Gray Flannel Suit could not have been more different. A wordy adaptation of a bestselling novel about the life of a business executive (referenced in season two of Mad Men), it starred Gregory Peck as a man struggling with the pressures of working for a New York television network whilst haunted by memories of the men he killed in combat. Even though its running time was 156 minutes, the film did not require a great deal of music. Herrmann provided a score dominated by strings. The standout moment (innocuously titlted “The Coat”) is a four and a half minute sequence that uses muffled timpani to ratchet up the tension for a flashback in which Peck’s character kills a young German sentry. This is one of the eight tracks that can be heard on Bernard Herrmann At Fox Volume 1 (VSD-6052).

Although the title of Herrmann’s second film of 1956 had an echo of the Hitchcock thriller he had just completed, The Man in the Gray Flannel Suit could not have been more different. A wordy adaptation of a bestselling novel about the life of a business executive (referenced in season two of Mad Men), it starred Gregory Peck as a man struggling with the pressures of working for a New York television network whilst haunted by memories of the men he killed in combat. Even though its running time was 156 minutes, the film did not require a great deal of music. Herrmann provided a score dominated by strings. The standout moment (innocuously titlted “The Coat”) is a four and a half minute sequence that uses muffled timpani to ratchet up the tension for a flashback in which Peck’s character kills a young German sentry. This is one of the eight tracks that can be heard on Bernard Herrmann At Fox Volume 1 (VSD-6052).

The Wrong Man

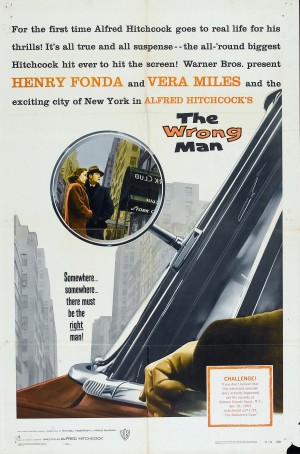

The third ‘man’ Herrmann wrote music for in 1956 was The Wrong Man. Based on a true story of mistaken identity and wrongful arrest, the film (shot in bleak monochrome with a documentary-like sense of realism) was an anomaly in the Fifties Hitchcock canon of glossy colourful suspense pictures. Although the director was dealing with familiar themes, his approach was quite radical. Even his normally playful cameo appearance (like an artist’s signature in the corner of a canvas) was expanded into a direct-to-camera address to the audience before the main credits and shot in Expressionist silhouette.

The third ‘man’ Herrmann wrote music for in 1956 was The Wrong Man. Based on a true story of mistaken identity and wrongful arrest, the film (shot in bleak monochrome with a documentary-like sense of realism) was an anomaly in the Fifties Hitchcock canon of glossy colourful suspense pictures. Although the director was dealing with familiar themes, his approach was quite radical. Even his normally playful cameo appearance (like an artist’s signature in the corner of a canvas) was expanded into a direct-to-camera address to the audience before the main credits and shot in Expressionist silhouette.

Henry Fonda played the role of Manny Balestrero, a bass player in New York’s Stork Club band, who is arrested on suspicion of robbery when he is falsely identified by a witness. The film charts his ordeal to clear his name and the disintegration of his marriage that resulted from the stress of the experience. Apart from a jaunty rhumba that opens and closes the film in a deliberate counterpoint to the unrelenting bleakness of the story, Herrmann scored the picture with a spare orchestration that is often reduced to a gnawing plucked double bass. Some of the cues (“The Cell II”) scream with a tension that threatens to snap under the strain. Following Samuel Fuller’s dictum (“Life’s in colour, but black and white is more realistic.”), Herrmann drained his orchestral palate and produced a work of musical monochrome.

Even though the full score runs to a modest thirty eight minutes, it can be a tough listen. Elmer Bernstein recorded the sassy prelude on his tribute disc to Herrmann, but for those with stout hearts you can get the original soundtrack on the FSM label (FSM Vol.9 No.7). Just make sure you don’t leave any cut-throat razors lying about when you listen to it.

Williamsburg: The Story of a Patriot

Williamsburg: The Story of a Patriot was made not for the cinemas but for a museum. The thirty-five minute film tells a fictional story to explain the state of Virginia’s role in the fight for American Independence, and is still shown regularly at the Colonial Williamsburg Visitor Centre. The film was produced by Paramount (Hitchcock’s studio for much of the Fifties) and Herrmann took on the project eagerly. The story of a Virginian planter (played by Hawaii Five O’s Jack Lord) allowed Herrmann to indulge in his love of eighteenth century music. He wrote sprightly hornpipes (“Overture”) and delightful minuets (“Gown and Court”) that look forward to the English music of The Three Worlds of Gulliver, and – with the spirit of Charles Ives no doubt looking over his shoulder – employed variations of “Yankee Doodle” (“The Drummer”) to signal the approach of war. So enjoyable was the experience of scoring the short film that Herrmann declined to take a fee for the work.

The full score (which is almost as long as the entire film’s running time) is available on a Tribute Film Classics disc as a companion to The Kentuckian (TFC 1004).

A Hatful of Rain

By the mid Fifties Herrmann was writing regularly for television. He provided stock cues for the CBS music library in the form of a “Western Suite”, “The Outer Space Suite” (channeling his own groundbreaking SF score for The Day the Earth Stood Still) and more “musical scenery” in the form of “The Desert Suite”. He wrote for episodes of Gunsmoke, The Virginian and Have Gun Will Travel, and miscellaneous scores for the Kraft Suspense Theater. All this kept him busy and in 1957 he had time for only one film score, A Hatful of Rain.

By the mid Fifties Herrmann was writing regularly for television. He provided stock cues for the CBS music library in the form of a “Western Suite”, “The Outer Space Suite” (channeling his own groundbreaking SF score for The Day the Earth Stood Still) and more “musical scenery” in the form of “The Desert Suite”. He wrote for episodes of Gunsmoke, The Virginian and Have Gun Will Travel, and miscellaneous scores for the Kraft Suspense Theater. All this kept him busy and in 1957 he had time for only one film score, A Hatful of Rain.

Based on a Broadway play, it was – for its time – a frank examination of morphine addiction. Two years earlier had seen the release of The Man with the Golden Arm, which had dealt with the same topic (but a different drug), and which is now remembered mostly for its striking Saul Bass title design and Elmer Bernstein’s jazz-influenced score. Herrmann chose to take another route in depicting the horror of addiction, writing a see-sawing string figure overlaid with screaming horns and nervous flutterings for wind that suggests the vicious spiral in which the film’s main character is caught. Legend has it that the first version of the movie’s main title music was thought to be too frightening and had to be toned down.

Twenty six minutes of the score is available in the form of a suite on Bernard Herrmann at Fox Vol 1 (VSD-6052).

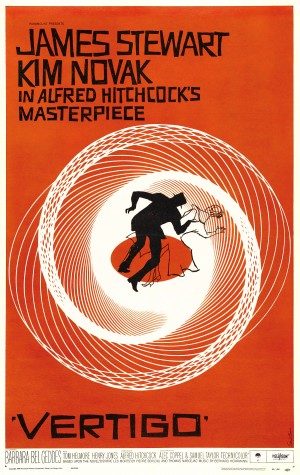

Vertigo

Although now rightly recognised as one of cinema’s true masterpieces (along with Citizen Kane it’s guaranteed to make all but the most contrary of filmgoers’ top ten), Vertigo was not always held in such high regard. On its release in 1958, critical reception was cool. There was praise for the film from some quarters, but it was muted. The reviewer of Time magazine famously dismissed it as “another Hitchcock and bull story”, showing that a critic is always ready to make a lame pun at the expense of insight. The New Yorker called it “far-fetched nonsense” whilst the Los Angeles Times complained that the plot was “hard to grasp at best”. Many reviewers of the time faulted the movie for its pacing, calling it too slow and “not a little confusing”. It’s true that its story was unconventional. Retired police detective Scottie Fergueson (James Stewart) is given the job of following the glacially beautiful Madeliene, who is suspected by her husband of harbouring suicidal tendencies. When Scottie’s intervention leads to Madeleine’s death, he is consumed with grief and can only find solace by trying to recreate her image in another woman he meets seemingly by chance.

Although now rightly recognised as one of cinema’s true masterpieces (along with Citizen Kane it’s guaranteed to make all but the most contrary of filmgoers’ top ten), Vertigo was not always held in such high regard. On its release in 1958, critical reception was cool. There was praise for the film from some quarters, but it was muted. The reviewer of Time magazine famously dismissed it as “another Hitchcock and bull story”, showing that a critic is always ready to make a lame pun at the expense of insight. The New Yorker called it “far-fetched nonsense” whilst the Los Angeles Times complained that the plot was “hard to grasp at best”. Many reviewers of the time faulted the movie for its pacing, calling it too slow and “not a little confusing”. It’s true that its story was unconventional. Retired police detective Scottie Fergueson (James Stewart) is given the job of following the glacially beautiful Madeliene, who is suspected by her husband of harbouring suicidal tendencies. When Scottie’s intervention leads to Madeleine’s death, he is consumed with grief and can only find solace by trying to recreate her image in another woman he meets seemingly by chance.

Vertigo performed respectfully at the box office, coming in at twenty first place when Hollywood totalled its ticket sales for the year, but it wasn’t the hit that Hitchcock had hoped for. Paramount re-released it in 1963 to cash in on the anticipation surrounding The Birds, and then in the late Sixties, under the terms of his Paramount contract, the director gained control of the rights. By 1974 Vertigo had been withdrawn completely from circulation and for a decade it was like a unicorn, much talked about but never seen. It could be glimpsed in stills that illustrated the growing library of books that were being written about the Master of Suspense, who was now approaching the end of his career and his life. Serious critics such as Robin Wood and Raymond Durgnat championed the film, even though they had to rely on an unreliable memory to do so.

By the time Vertigo was re-released in 1984 (along with other ‘lost’ Hitchcocks, Rear Window, The Trouble with Harry, Rope and The Man Who Knew Too Much) it trailed behind it a fabled reputation. I was living in Japan at the time and I took a bullet train to Hiroshima to watch it on a double bill with The Man Who Knew Too Much. I still have the snapshot I took of the cinema where it was playing. Sitting in the darkened theatre listening to the swirling strings and dark brass chords of the opening “Prelude” made the hairs on the back of my neck stand up, and the moment at the end when the nun steps out of the shadow like a ghost to the accompanient of an spooky organ literally made me jump.

I was familiar with the score long before I saw the movie. The five minute “Scene D’Amour” was a standard on Herrmann compilations. In the film the music accompanies the scene where Judy completes her transformation into Madeleine in the Empire Hotel. She emerges from the bathroom in her grey tailored suit with her hair pinned up and is bathed in the eerie green light of the hotel’s neon sign. As Scottie takes her in his arms, the camera circles the couple and Herrmann’s music swells into a grand romantic statement. I listened to Herrmann long before I listened to Wagner and so for a long time wasn’t aware of the borrowing (or, indeed, the significance) of the theme from the opera Tristan and Isolde.

Hitchcock provided his composer with notes on music suggestions and the sound mix, but on the whole gave him a free hand. The notes the director made for his sound editor for the scene reveal the confidence he had in Herrmann’s ability to carry the moment:

“When Judy is in the bathroom changing – we just hear faint traffic noises, and when she emerges and we go into the love scene we should let all traffic noise fade, because Mr Hermann [sic] may have something to say here. For the rest of the sequence we will hear faint traffic noises, except when we go away to the portrait (when Mr Herrman [sic] will be the one to take over.)”

Herrmann went his own way with the music. His use of habanera rhythms to portray the sad and mysterious Carlotta was inspired not by the Spanish mission setting but by his belief that the film should have been filmed in a different locale and with a different lead actor. “They should never have made it in San Francisco, and not with Jimmy Stewart,” he said. “It should have been an actor like Charles Boyer. It should have been left in New Orleans, or in a hot, sultry climate. When I wrote the picture, I thought of that.”

For the celebrated zoom in/track back shot that Hitchcock employed to convey Scottie’s acrophobia, Herrmann wrote a disorientating chord overlaid with frenzied harp glissandi. It may not be as famous a musical moment as the stabbing strings of Pyscho, but it has a similarly jolting effect.

The version of the score I’m listening to right now is the Joel McNeely re-recording on the Varese Sarabande label (VSD-5600). The original soundtrack conducted by Muir Mathieson is also available on a Varese Sarabande CD (B000024Q93) and has the added bonus of the cool Saul Bass poster design on its cover.

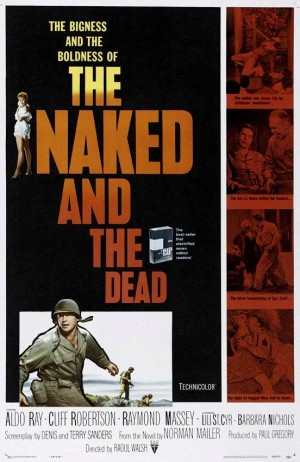

The Naked and The Dead

The Naked and the Dead was a war movie based on Norman Mailer’s uncompromising autobiographical first novel published in 1948. The writer’s own experience of combat in the Pacific was much more limited than his book suggested, but the novel was well received and established Mailer’s reputation as a hard-hitting realist. The film version was originally to have been directed by Charles Laughton, but when his first (and only) feature as director Night of the Hunter bombed at the box office, the megaphone was passed on to Raoul Walsh. Walsh had directed James Cagney in some of his greatest gangster roles. He wore a black patch to hide a car crash injury which had cost him his right eye.

The Naked and the Dead was a war movie based on Norman Mailer’s uncompromising autobiographical first novel published in 1948. The writer’s own experience of combat in the Pacific was much more limited than his book suggested, but the novel was well received and established Mailer’s reputation as a hard-hitting realist. The film version was originally to have been directed by Charles Laughton, but when his first (and only) feature as director Night of the Hunter bombed at the box office, the megaphone was passed on to Raoul Walsh. Walsh had directed James Cagney in some of his greatest gangster roles. He wore a black patch to hide a car crash injury which had cost him his right eye.

Mailer’s book was too strong for the screen so it was watered down by the screenwriters, and not even Herrmann’s suitably militaristic score could beef it back up again. As of writing there are plans for a new recording of the score. The “Prelude”, which I’m listening to right now, is at the beginning of disc two of Silva Screen’s compilation The Essential Bernard Herrmann Film Music Collection (FILMXCD 308). To my ears, it sounds a lot like some of the battle cues in Jason and the Argonauts.

The Seventh Voyage of Sinbad

The Seventh Voyage of Sinbad was the first of four films that Herrmann would score for producer Charles Schneer – the other three were The Three Worlds of Gulliver, Mysterious Island, and Jason and the Argonauts. Nobody calls these movies Charles Schneer pictures – they call them after the name of their special effects supervisor, Ray Harryhausen.

The Seventh Voyage of Sinbad was the first of four films that Herrmann would score for producer Charles Schneer – the other three were The Three Worlds of Gulliver, Mysterious Island, and Jason and the Argonauts. Nobody calls these movies Charles Schneer pictures – they call them after the name of their special effects supervisor, Ray Harryhausen.

The wizard of Dynamation became fascinated by the possibilities of fantasy cinema when, as a young boy, he saw the original King Kong. Like Steven Spielberg and Perter Jackson (both of whom cite his influence on their own work), Harryhausen spent his boyhood experimenting with film, making animated shorts in his father’s garage. He honed his skills in the Army Motion Picture Unit during the war under the command of film director turned colonel Frank Capra. His first major Hollywood project was Mighty Joe Young, the story of a giant ape, and he followed this with The Beast from Twenty Thousand Fathoms, which was about a beast from twenty thousand fathoms.

Both these pictures were shot in black and white, but by the end of the Fifties Harryhausen had graduated to colour, a decision which would present him with all new kinds of technical challenges. Rather than continue making movies about monsters in the real world, Harryhausen looked to ancient legend for his first colour feature. The Seventh Voyage of Sinbad was the first of three Sinbad movies that Harryhausen would make over a period of almost twenty years, but, sadly, it was the only one that would be scored by Herrmann (the other two went to Miklos Rosza and Roy Budd).

Herrmann explained his approach to the project in the liner notes for The Fantasy Film World of Bernard Herrmann (B000000IUQ). “The music I composed had to reflect a purity and simplicity that could be easily assimilated to the nature of the fantasy being viewed. By characterizing the various creatures with unusual instrument combinations … and by composing motifs for all the major characters and actions, I feel I was able to envelop the entire movie in a shroud of mystical innocence.”

The film’s main title sequence – a tapestry of marvellous images and fabulous creatures – is scored with an Oriental-style overture, which contains the kernel of the love theme that Herrmann would later develop for Hitchcock’s Marnie. This segues into a moody dirge (“The Fog”) – reminiscent of the opening of Rachmaninoff’s The Isle of the Dead – as Sinbad’s ship appears out of the night. I sometimes put this cue on repeat and listen to it over and over again. The score is like a treasure chest, overflowing with soft pearls (“The Princess”) and glittering diamonds (“The Egg”). It also has its fair share of sturm und drang in the music for the Cyclops, the Roc, and the Dragon. A duel between Sinbad and a grinning skeleton is given a frantic xylophone scherzo, which – on the original soundtrack, at least – is played at a breakneck speed.

I have two versions of the score: the original soundtrack on the Soundtrack Library (CD 62), which I think is a bootleg; and the Varese Sarabande re-recording by John Debney (VSD-5961), which came in for a lot of stick from Herrmann purists for taking some of the cues at too slow a tempo. There’s no pleasing the Herrmann purists. In the interests of fairness, I’ve just played the two discs back to back, and I have to say that I prefer the Debney.

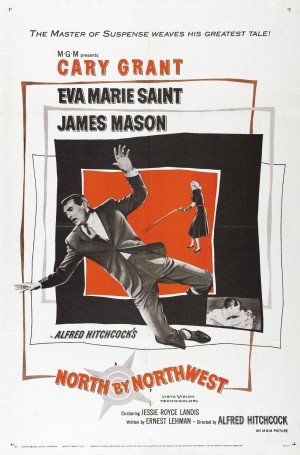

North By Northwest

In North By Northwest Mad man Roger Thornhill (played with suave elegance by Cary Grant) is “mistaken for a much shorter man” and pursued across America by a group of fifth columnists. The plot, which involved planes and trains and automobiles, was as preposterous as it was inspired, and screenwriter Ernest Lehman mixed the elements of intrigue, romance, suspense and comedy into a perfect cocktail with a wit as dry as a Gibson. It was, in fact, Herrmann who had introduced the writer to Hitchcock (“I’ve got to get you and Hitch together,” the composer said. “I think you would hit it off very well.”). Lehman was not the originator of the story for North By Northwest (the idea of a man assuming the identity of a fake masterspy had been gifted to Hitchcock by journalist Otis Guernsey, who had himself based his underdeveloped treatment of it on a real incident that happened in the Middle East in World War Two). During long story conferences with the director, Lehman shaped and polished the script until it purred and gleamed.

In North By Northwest Mad man Roger Thornhill (played with suave elegance by Cary Grant) is “mistaken for a much shorter man” and pursued across America by a group of fifth columnists. The plot, which involved planes and trains and automobiles, was as preposterous as it was inspired, and screenwriter Ernest Lehman mixed the elements of intrigue, romance, suspense and comedy into a perfect cocktail with a wit as dry as a Gibson. It was, in fact, Herrmann who had introduced the writer to Hitchcock (“I’ve got to get you and Hitch together,” the composer said. “I think you would hit it off very well.”). Lehman was not the originator of the story for North By Northwest (the idea of a man assuming the identity of a fake masterspy had been gifted to Hitchcock by journalist Otis Guernsey, who had himself based his underdeveloped treatment of it on a real incident that happened in the Middle East in World War Two). During long story conferences with the director, Lehman shaped and polished the script until it purred and gleamed.

North By Northwest was made at MGM – a studio known for its class and sophistication – and Herrmann’s propulsive score began before the familiar lion mascot had finished its roar. Over an image of intersecting green lines (designed by Saul Bass, and anticipating the Psycho credits) the orchestra plays the “Overture”, a dizzying fandango that the composer wrote for “the crazy dance about to take place between Cary Grant and the world.” There is, indeed, something almost balletic in the way in which Grant moves. Watch how nimble and graceful he is when he escapes his hospital prison by climbing out onto the ledge and sneaking out through a neighbour’s room. This scene, incidentally, contains one of my favourite moments in the movie when the startled female patient cries out for the intruder Thornhill to “Stop!”, puts on her glasses and then repeats the word in a more inviting tone.

The script crackles with good dialogue (“Something wrong with your eyes?” “Yes, they’re sensitive to questions.” / “How does a girl like you get to be a girl like you?” “Lucky, I guess.”), the editing is razor sharp, the photography has a bright sheen that brings out the richness of the Technicolor, and the actors are tailored to within an inch of perfection (Grant is The Man in the Grey Kilgour Suit). Eva Marie Saint is the epitome of the icy Hitchcock blonde (a million miles away from her kitchen-sink performances of A Hatful of Rain and On the Waterfront). James Mason, as the diabolically named Vandamm, is the urbane villain whose velvety voice commands his lovesick second in command Leonard to commit unspeakable acts. Nobody involved in this movie – from the director down to the key grip – puts a foot wrong.

Herrmann was on form, too. His score may be a little monothematic – tellingly, he chose only to include an extended version of the overture for his Great Hitchcock Movie Thrillers disc and resisted arranging a suite of music from the film. That’s not to say that it’s all about the fandago. There’s a nervous suspense theme woven throughout the score that sounds like a spy’s Morse code message, some dark growling brass (“Car Crash”), and a lilting love theme (“Conversation Piece”) which gently rocks to the rhythms of the Twentieth Century sleeper car.

As significant as the music Herrmann provides are the moments that he chooses to leave unscored. In the film’s most celebrated scene Roger Thornhill waits to meet the mysterious Kaplan at an isolated bus stop and is menaced by a crop dusting bi-plane. The sequence has a slow burn build-up and a dynamite finish, and it plays out without a note of music. Herrmann, in fact, wrote a cue (“The Highway”) for the start of the sequence, but it did not make it to the final cut. In its use of muffled timpani it recalls “The Coat” cue from The Man in the Gray Flannel Suit.

The North By Northwest “Overture” is one of the usual suspects that is rounded up for any Herrmann compilation. The original sountrack was released on the Turner Classic Movies label (8 36025 2) and, for medium-level completists, includes source music and outtakes. Full blown completists also need to own the Varese Sarabande re-recording by Joel McNeely (VCL 1107 1067) as it contains the “previously unreleased” cue “The Highway” and an alternate version of “The Station” cue. This is obviously more information than you will ever need to know. I am not a Herrmann completist, but I have both discs, which I have just listened to back to back, and I now feel a sudden urge to go and watch my DVD of the film (which, incidentally, has an isolated film score track).

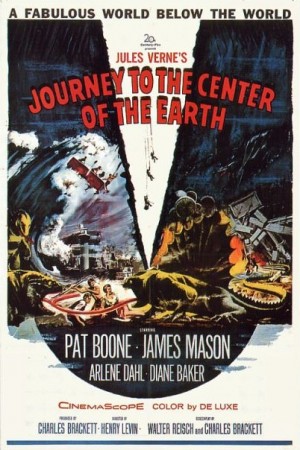

Journey to the Centre of the Earth

Journey to the Centre of the Earth was based on a novel by the prolific “Father of Science Fiction” Jules Verne. Disney had had a hit with 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea (after White Christmas it was the highest grossing film of 1954), and Twentieth Century Fox hoped to replicate the success with an adaptation of Verne’s subterranean adventure. James Mason, who had played Captain Nemo in the Disney picture, was cast as Professor Oliver Lindenbrook, and was given cheery support by Pat Boone and Arlene Dahl. Together with the tight-lipped Hans (played by Icelandic born Olympic athlete Pétur Rögnvaldsson) and his duck Gertrude, they journey to the centre of the earth (the clue is in the title) where they find giant lizards and the lost city of Atlantis.

Journey to the Centre of the Earth was based on a novel by the prolific “Father of Science Fiction” Jules Verne. Disney had had a hit with 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea (after White Christmas it was the highest grossing film of 1954), and Twentieth Century Fox hoped to replicate the success with an adaptation of Verne’s subterranean adventure. James Mason, who had played Captain Nemo in the Disney picture, was cast as Professor Oliver Lindenbrook, and was given cheery support by Pat Boone and Arlene Dahl. Together with the tight-lipped Hans (played by Icelandic born Olympic athlete Pétur Rögnvaldsson) and his duck Gertrude, they journey to the centre of the earth (the clue is in the title) where they find giant lizards and the lost city of Atlantis.

Although there was some location shooting at the Carlsbad Caverns National Park in New Mexico, most of the film was made on sound stages, and to a modern audience the rock does look a bit too much like cardboard at times. The film was a hit with the audience of its day and in the Sixties was a staple of TV schedules, thrilling a generation of children long before the advent of CGI.

In the liner notes to his 1974 album The Fantasy Film World of Bernard Herrmann, the composer elaborated on his approach. “I decided to evoke the mood and feeling of inner Earth by using only instruments played in low registers. Eliminating all strings, I utilized an orchestra of woodwinds and brass, with a large percussion section and many harps. But the truly unique feature of this score is the inclusion of five organs, one large cathedral and four electronic. These organs were used in many adroit ways to suggest ascent and descent, as well as the mystery of Atlantis.” Herrmann omits to say that he also included the serpent – the instrument he had used in White Witch Doctor – to portray the attack of a giant chameleon.

Just as Beneath the Twelve Mile Reef can be seen as a tone poem to the sea, so Journey is a hymn to the underworld. Malevolent and brooding (“Explosions/The Message”), epic and inspiring (“Mountain Top/Sunrise”), violent and terrifying (“The Dimetroden’s Attack”), ethereal and moving (“The Lost City/Atlantis”) – Herrmann’s score is all these things. There are even moments of light relief provided by Pat Boone, whose contract no doubt included a clause about his singing a couple of songs, which he does (“Twice as Tall” “The Faithful Heart”). These were written by songwriting duo James Van Heusen and Sammy Cahn and were filmed and recorded, but edited out of the final cut of the film.

Herrmann arranged a suite of the music for his 1974 album, but if you really want to immerse yourself in the depths of the score you need to listen to the original soundtrack on Varese Sarabande (VSD-5849). It has just come to a crashing end on my stereo.

Blue Denim

Blue Denim, controversial and daring at the time of its release, now seems as ridiculous and as dated as Fifties slang ( Cool it, Pops! Hey Daddy-O!). Based on a play by Midnight Cowboy author James Leo Herlihy, it dealt with the issues of teenage pregnancy and abortion. The film was directed by Philip Dunne, who was mystified as to why his friend Herrmann agreed to do the picture. The score has been described as “Baby Vertigo” for its melodic similarities to the Hitchcock movie and for its overbearing presence in the drama. I’ve not heard it and have never felt compelled to buy the soundtrack, which is available on an FSM release (FSM Vol. 4, No. 15).

Blue Denim, controversial and daring at the time of its release, now seems as ridiculous and as dated as Fifties slang ( Cool it, Pops! Hey Daddy-O!). Based on a play by Midnight Cowboy author James Leo Herlihy, it dealt with the issues of teenage pregnancy and abortion. The film was directed by Philip Dunne, who was mystified as to why his friend Herrmann agreed to do the picture. The score has been described as “Baby Vertigo” for its melodic similarities to the Hitchcock movie and for its overbearing presence in the drama. I’ve not heard it and have never felt compelled to buy the soundtrack, which is available on an FSM release (FSM Vol. 4, No. 15).

Around the time that Herrmann was busy with this project, he started writing for the cult TV series The Twilight Zone, the first episode of which aired in October 1959. Mention the name of the show to anyone and they’re likely to respond with an imitation of the famous theme (Di-di-di-di, Di-di-di-di), which has become an aural meme for anything spooky or unexplained. Herrmann, however, did not write this piece of music (it was composed for the second season by Romanian-born Marius Constant) and provided his own creepy “Main Title”. Over a four year period Herrmann wrote scores for seven episodes. Working on a small television budget, the composer wrote for small pared-down orchestras – for the Living Doll episode, it was just a bass clarinet, two harps and a celeste – and effectively produced a series of other-worldly chamber pieces. The most celebrated is the gorgeous Walking Distance, written for a string ensemble and a harp, whilst the most curious is the repetitive tick-tock of 90 Years Without Slumbering. Working to tight deadlines, Herrmann could be forgiven for recycling some of his dark materials, but his inventiveness never flagged.

All the scores have been re-recorded (and, in some cases, reconstructed) and are available on a Varese Sarabande disc (VSD2-6087). Right now I’m listening to the ghostly vibraphones of Eye of the Beholder.

![The Man Who Knew Too Much – 4K restoration / Blu-ray [A]](http://www.bernardherrmann.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/TMWKTM-4K.jpeg)

![The Bride Wore Black / Blu-ray [B]](http://www.bernardherrmann.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/07/BrideWoreBlack.jpeg)

![Alfred Hitchcock Classics Collection / Blu-ray [A,B]](http://www.bernardherrmann.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/AHClassics1.jpg)

![Endless Night (US Blu-ray) / Blu-ray [A]](http://www.bernardherrmann.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/EndlessNightUS.jpg)

![Endless Night (UK Blu-ray) / Blu-ray [B]](http://www.bernardherrmann.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/12/ENightBluRay.jpg)