Written by David Raksin.

Produced by Stephen D. Paley for CBS News.

Broadcast nationally, USA, September 1976.

Running time approx. 28 minutes.

(Film clip: opening credits of North by Northwest with titles for CAMERA THREE. Clip concludes with the appearance of Alfred Hitchcock missing the bus)

David Raksin: The moment in every Hitchcock film in which the master himself appears.

Raksin: As everyone knows he was the portly gentleman who just missed the bus. Today on Camera Three we will be concentrating not on the visual aspect of films, rather on the soundtrack: specifically on the composer who wrote the brilliant music you have just heard, my friend and colleague, Bernard Herrmann. My name is David Raksin and I am a film composer.

In the music that begins North by Northwest, the composer is dealing with a city obsessed with its own activity. The city is New York, the essential American metropolis. It is a mark of Herrmann’s approach to films, that instead of writing ‘city-music’ — whatever that is — he composed a fandango, a Spanish dance, complete with tambourines, which starts the film off with a burst of energy.

David Raksin on the set of Camera Three

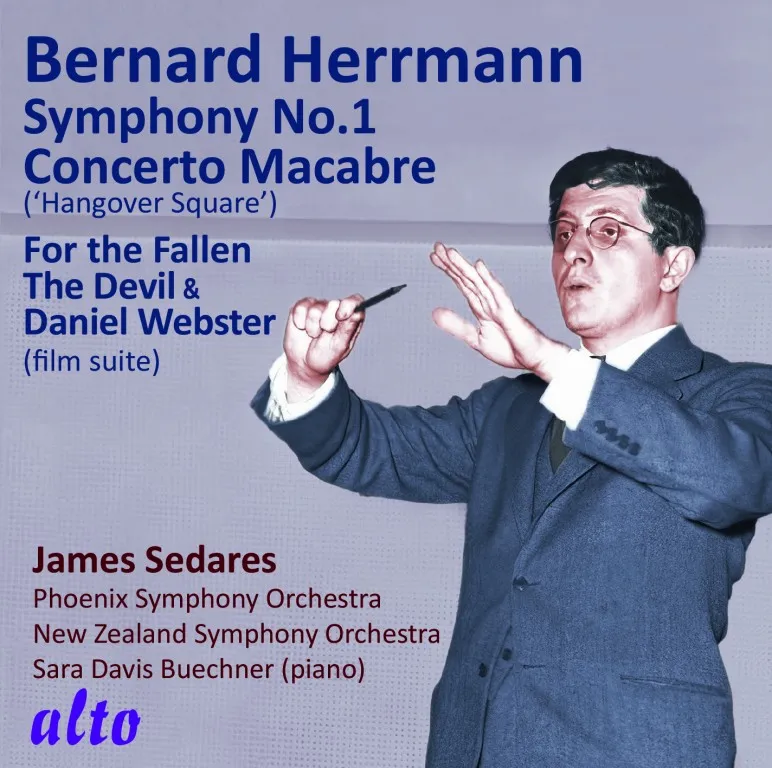

I first met Benny Herrmann in 1935 at the old CBS Radio studios on Madison Avenue. He was then a junior member of the conducting staff having studied at Juilliard. Even then his knowledge of obscure music was awesome; in the 30s when hardly anyone knew who Charles Ives was, Benny conducted six weeks of radio concerts of Ives’ music. During those years Benny also composed an enormous amount of concert music including: three ballets; a sinfonietta; a symphony; a violin concerto; a cantata, “Moby Dick”, which was performed by The New York Philharmonic; and music for radio dramatic programs, 1200 of them!

At CBS he worked with Orson Welles and John Houseman on the Mercury Theater of the Air. Welles and Herrmann got on so well that when The Amazing Orson went to Hollywood to film Citizen Kane, he invited Benny to compose the music.

(Film clip of opening of Citizen Kane with music)

Raksin: Few of us are likely to forget the opening of that film, and the music that leads us into the grandiose and morbid world of Charles Foster Kane.

(Film clip continues with Kane’s death)

Kane: “Rosebud.”

(End film clip)

Raksin: To illustrate the failure of the singing career of Kane’s second wife, Susan Alexander, Herrmann composed an operatic aria, “Salammbo” and wrote the vocal parts so high it would sound strained and inept, the following result.

(Film clip of the Salammbo aria from KANE)

Stage director: “Places everybody…places, please!”

Susan Alexander: “Oh, cruel…”

(End of KANE clip)

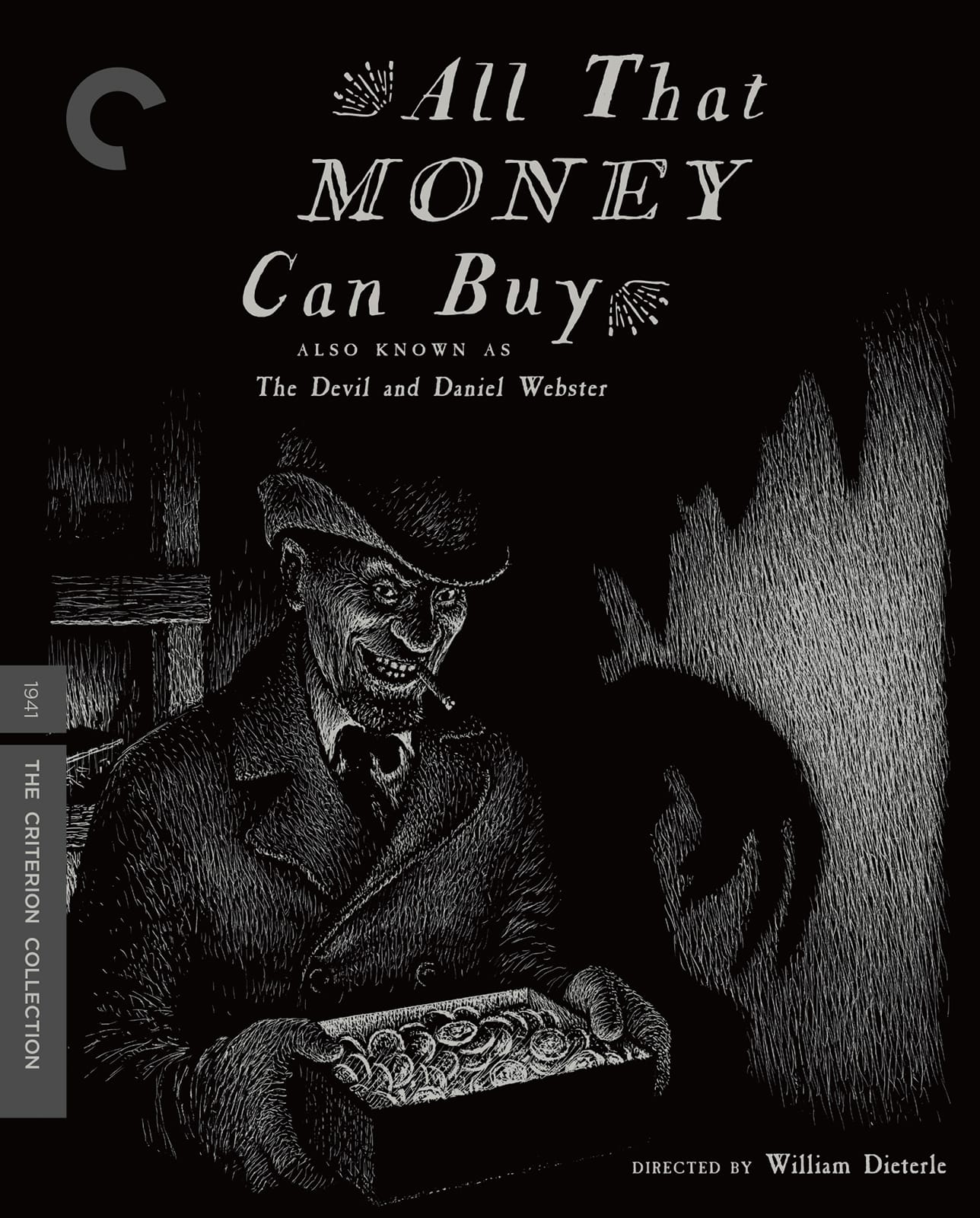

Raksin: During the year of Citizen Kane, Herrmann also composed the score of All That Money Can Buy, the film version of The Devil and Daniel Webster for which he won his only Academy Award. Two years later he wrote the music for Jane Eyre, in which Elizabeth Taylor made an unheralded appearance. The film was directed by Robert Stevenson, from a script by Aldous Huxley, John Houseman and Stevenson. Orson Welles played the role of Edward Rochester.

(Start of clip from Jane Eyre)

Raksin: The ominous presence of Rochester as he appears astride his black horse is wonderfully conveyed by the dark colors of the music, a Herrmann trademark.

(Continue film clip)

(End clip)

Raksin: Benny’s affinity for dark and mordant sounds was recognized by the studios and found expression once again in Hangover Square. This film is about a composer who suffers from amnesia, and who has committed several murders while under its influence. He has been working on a piano concerto throughout the story and the film culminates with its performance…but too late, for he has gone mad.

(Film clip from Hangover Square of the final fire in the concert hall)

Bone: “You must hear the concerto to the end.”

Voice: “Are you mad? Go back!”

Raksin: Herrmann actually composed a complete concerto movement, which has since been performed at concerts and recorded.

Mrs. Bone: “George, we have to get out of here. George. Get George! Father.”

Voice: “Listen, why didn’t you try to get out?”

Voice: “It’s better this way, sir.”

(End Hangover Square film clip)

(Start of clip from The Ghost and Mrs. Muir)

Raksin: Toward the end of Joseph Mankiewicz’s romantic fantasy The Ghost and Mrs. Muir, there is a sequence in which the director denotes the passage of time by showing first the stormy sea and then dissolving to the ensuing calm as Mrs. Muir walks alone upon the beach. The music speaks of the rushing waves, then of the solitude of Mrs. Muir.

(“The Late Sea” passage from The Ghost and Mrs. Muir)

Mrs. Muir: “Hello, Anna!”

(End film clip)

Raksin: Some of the themes from

Jane Eyre and

The Ghost and Mrs. Muir eventually appeared in Herrmann’s opera

Wuthering Heights which has never been staged, but which he finally recorded in 1966.

In The Day the Earth Stood Still a flying saucer from another planet has landed in Washington, and a spaceman has been killed by some soldiers. His robot, Gort, comes forth to avenge his master. Fortunately Patricia Neal has learned a phrase in space language with which to disarm the monster. Around the studio we used to go around saying, “Klaatu barada nikto.” Herrmann augmented his conventional orchestra by adding two theremins, an electronic violin and various other electronic instruments and produced an effect of rising tension by reiterating ominous chords and phrases, usually in the lower register of the orchestra.

(Clip from The Day the Earth Stood Still)

Neal: “Gort, Klaatu barada nikto…Klaatu barada nikto.”

(End film clip)

Raksin: In Beneath the Twelve Mile Reef Herrmann has to compose music for many underwater sequences. In one of which a diver was attacked by a giant octopus. Benny was always getting stuck with music for monsters, probably because he handled them so well. In this case he used an orchestra which included nine harps.

(Clip of octopus attack from Beneath the Twelve Mile Reef)

(End clip)

Raksin: Aside from his association with Orson Welles, Herrmann is probably best known for his work with Alfred Hitchcock. No other composer has so successfully captured the unique Hitchcock blends of mystery, suspense, the sardonic and the romantic. Herrmann’s only appearance on film was in Hitchcock’s second version of The Man Who Knew Too Much. He conducted the orchestra in the famous scene at Albert Hall, during which an assassination is attempted at the moment when the cymbals crash.

(Still film frames of Herrmann conducting from The Man Who Knew Too Much)

Raksin: When Herrmann came to the music for Psycho, he used an orchestra consisting only of strings and explained this self-imposed limitation by saying, ” In this way I was able to complement the black and white photography with a black and white sound.” How effective this ensemble could be in the hands of a master can be heard in the following sequences. In the first one, which was a favorite of Benny’s, there is a typical way in which he was able to evoke tension with the simplest of means.

(Raksin sits at the piano)

Raksin: This is a page from the orchestra score for Psycho. The music is based on a four note phrase which is played by the first violins….

(Raksin plays the piano)

Raksin: …while the second violins also play a repeating phrase…

(Raksin plays the piano)

Raksin: …together they sound something like this….

(Raksin plays the piano)

Raksin: By repeating this simple rhythmic pattern together with a melodic line in synchronization with the windshield wipers of Janet Leigh’s automobile, Herrmann is able to maintain the tension at a frantic pitch.

(Film clip of Marion Crane driving in the rain storm. End Clip)

Raksin: When you think of Psycho the two murder sequences always come to mind. In the second of these Herrmann introduces one of his most original effects, by combining a pizzicato tremolo –which is a kind of strumming sound — with eerie harmonics high on the violins. Suddenly there are a series of shrieks, which are produced by the violins and violas playing in major sevenths….

(Raksin plays the piano)

Raksin: …and minor ninths…

(Raksin plays the piano)

Raksin: ….in the extreme upper register…

(Raksin plays the piano)

(Film clip of Arbogast approaching the house. Clip continues to the murder on the stairway. End Clip)

Raksin: A few years after composing this remarkable score, Herrmann left Hollywood. Disillusioned and unable to find work, he went to live in England for which he always had an affinity. Benny’s kind of symphonic film music had been superseded by the commercial song, and pop music was being used in place of traditional film scoring. Francois Truffaut, because of his familiarity with the films of Alfred Hitchcock, knew and admired Benny’s music. He became the first of the new generation of filmmakers to seek Herrmann out, and he was rewarded with two brilliant scores,

Fahrenheit 451 and

The Bride Wore Black.

Other assignments soon followed: For Brian DePalma he composed Sisters and Obsession; for Larry Cohen, who became his close friend he composed the score for It’s Alive. Benny used to say exultantly, “The new guys, they want me!” And so they did. But what a world of sadness we can sense beneath his realization that the years of neglect were finally over.

Herrmann’s last film score was for Martin Scorsese’s Taxi Driver. The years had cost him his health. But for this final effort he summoned up all his energy and talent and composed a score that was in many ways unlike anything he has composed before. Here is the main title music of Taxi Driver, with its powerful evocation of New York as hell.

(Film clip: opening titles of Taxi Driver)

(Ringing phone in film clip)

Voice: “Larry, answer that!”

(End film clip)

Raksin: Taxi Driver ends with a strange and ambiguous episode, in which Robert DeNiro drives his cab away into the jungle that is New York at night. It leaves you wondering what the director meant. Did Scorsese mean that this living time bomb was free to roam the streets till he exploded again? Suddenly three powerful notes rang out on the soundtrack….

(Three second clip from Taxi Driver)

Raksin: …and we knew at least what Bernard Herrmann was thinking. For those three notes were the ones you heard in Psycho, when Benny wanted to signal that we are in the presence of a dangerous and demented man.

(Three second clip from Psycho)

Raksin: When the final orchestra sessions for Taxi Driver were finished there still remained one more cue for a small jazz group which they planned to record a few days later. For some reason Benny suddenly changed his mind and insisted on recording it before he left the studio. Then, exhausted, he returned to his hotel, and that night he fell into a deep sleep from which he never awakened.

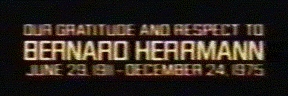

(Frame still of the dedication at the end of Taxi Driver)

Raksin: In the three quarters of a century during in which films have been made this is the only instance of such a dedication.

(End titles of CAMERA THREE with main title music from Vertigo.)

![The Man Who Knew Too Much – 4K restoration / Blu-ray [A]](http://www.bernardherrmann.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/TMWKTM-4K.jpeg)

![The Bride Wore Black / Blu-ray [B]](http://www.bernardherrmann.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/07/BrideWoreBlack.jpeg)

![Alfred Hitchcock Classics Collection / Blu-ray [A,B]](http://www.bernardherrmann.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/AHClassics1.jpg)

![Endless Night (US Blu-ray) / Blu-ray [A]](http://www.bernardherrmann.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/EndlessNightUS.jpg)

![Endless Night (UK Blu-ray) / Blu-ray [B]](http://www.bernardherrmann.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/12/ENightBluRay.jpg)