Kurt Luchs: Can you share some of your thoughts on Herrmann as a composer? Why is his work so enduring in a field where so much work is so quickly dated?

John Morgan: One of the primary reasons for Herrmann’s continual popularity is that his unobtrusive style is currently in fashion. Of course, there are many more layers to Herrmann’s music than this dramatic trait that today’s composers simply don’t possess, but the nonspecific nature of his music to the action is simply today’s film music style. He was also very fortunate to have worked on several films that are regarded as being the prototype to contemporary film styles, such as Psycho and most notably, Taxi Driver.

KL: In your liner notes you talk of taping soundtracks right off the television as a child. At what age did you first become aware of Herrmann’s music? Was he always your favorite? Who are some others you admire, then and now?

Morgan: Steiner’s King Kong is the first film that really struck me musically and dramatically when I first saw it on television in the mid-fifties. Like many others, I came to initially know Herrmann through his marvelous fantasy scores of the late fifties and early sixties. Although I enjoy the music of many film composers, I would hate to pick a favorite. The masters are the ones who have written a body of work that I can’t imagine anyone else doing or equaling. I can honestly say that Herrmann, Steiner, Waxman, Rozsa, Newman (Alfred), Williams, Goldsmith, etc. have written scores I can not imagine being bettered. I would have the same trouble if someone were to ask me my favorite opera composer or ballet composer!

KL: When did you first encounter these two scores (Garden of Evil/Prince of Players), and what was your response at the time? How has your response changed over the years and especially as a result of working on the reconstruction and performance of these works with William Stromberg?

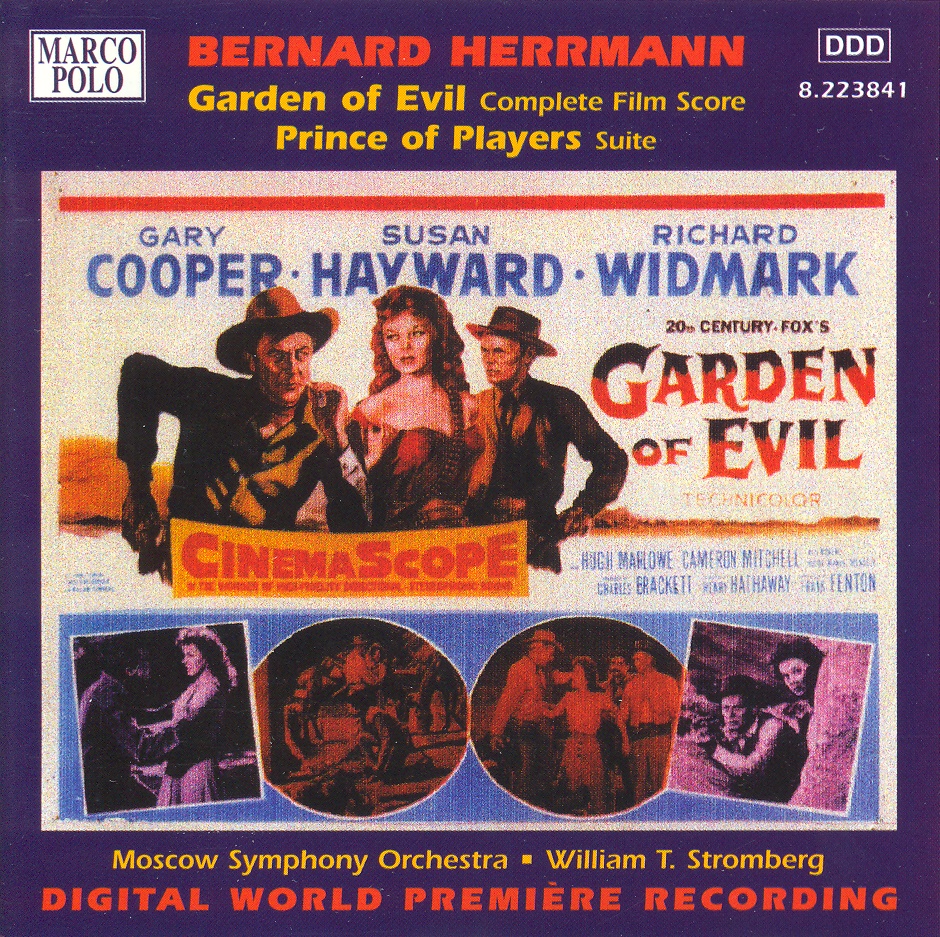

Morgan: Garden of Evil I first encountered on television. In fact, I have still never seen the film in CinemaScope or heard it in stereo! I came to this film later in my life after knowing the earlier work of Herrmann through his Decca recordings and those early Pye recordings. I had also thought Garden of Evil was a score that could hold up to a complete recording away from the film. Because of the nature of film music, some great film music doesn’t necessarily make great listening on its own as music. Often, Herrmann would create music that is really a cantus firmus to the sound effects and the music seems to miss something away from the sound effects. Not dramatically–it’s perfect that way, but in terms of taking the music out of the film and presenting it on its own. My feeling is that when we rerecord something for CD it ceases to be film music and must work purely as music. Saying that, I do think there are several scores that Herrmann composed that work as music in a complete form. Garden of Evil is one of them. I would also list Ghost and Mrs. Muir, Jane Eyre, Beneath the 12-Mile Reef and others. For instance, The Wrong Man is virtually a perfect film score for that particular film, but certainly listening to the entire music score on its own could be tedious for most people. Of course, I am a film music buff too, and I love hearing every note of every score I admire, but being a musician, I realize this music must work away from the film itself to have real commercial success on recordings.

KL: How do you think Garden of Evil fits in with Herrmann’s other work, being his only Western film score?

Morgan: Garden of Evil is really a lousy film in my estimation. Some of the dialog and delivery is so stilted it is laughable, but I think Herrmann turned in one of his most exciting and colorful scores. When a film was weak, Herrmann turned to some other quality of the film to get inspired. Being that this film was in stereo and had very colorful locations, I think he was inspired to write a vigorous and varied score. He would always grab on to something to inspire him musically, even if he wasn’t inspired by the dramatics in the film itself.

KL: What is its relation to his TV Western works–e.g., for the CBS stock library, The Virginian, etc.?

Morgan: I don’t really hear very much “western-type” music in this score. There is a portion of one cue that Bill Stromberg and I always kid about saying Tiomkin came in and “ghost” wrote it for Herrmann. It sounds like his tip of the hat to Tiomkin’s and Steiner’s western scores. Being that Garden of Evil is located in Mexico, one can certainly make a case for the sort of habanera rhythm that Herrmann employs, although he seems to employ that rhythm in virtually all his scores.

KL: How does Herrmann treat the Western differently from other film composers? My sense is that he avoids any number of cliches.

Morgan: Well, when Steiner composed music for 1939′s Dodge City, it wasn’t cliched western music then. Film cliches (or any cliche) come from overuse and when you have something that really works, other composers will put it in their bag of tricks and pretty soon it becomes tiresome and cliched. Certainly Herrmann’s music for Psycho‘s shower scene is now cliched from over use and even parodistic use. Frankly, there is little in the Garden of Evil score that has any extra musical associations with the western genre. It was just his style. I would say if you played 90% of this music to someone who knew nothing about the setting of this film, they would probably agree that it is an adventure type of film, but be unable to pinpoint any era or locale.

KL: To what extent do you feel you were able to duplicate the three-channel stereo effect of the original soundtrack in two channels? How did you do it?

Morgan: Since Herrmann indicated the orchestra seating and what channels of sound certain instrumental sections should emanate from, we set up the orchestra in the same fashion. So the center is really there as far as the listening experience, although it is a phantom center that equally combines right and left to make up a center. If you listen with earphones, you can hear some of the woodwinds and percussion playing off each other in different locations. That is why we needed three suspended cymbals and three bass drums spread across the room to get this wide separation.

KL: Talk about the restored cues a bit–what is here on your release that didn’t make it into the original film?

Morgan: Whenever timings didn’t work out, Herrmann’s music style always made it fairly easy to cut out bars here and there or to repeat bars when a cue came in too short. We didn’t do the added repeats, but we did restore the bars as we felt they were his final thoughts as written on the score. Also, musically speaking, doing the score as he first conceived it made for a finer sense of balance and fulfillment. The one completely cut piece that we restored is the third cue called THE START. It was evidently recorded, but dropped. I really have no idea why it was dropped; maybe re-editing of the film. It is a very rare film score by any composer that has no alterations or deletions.

KL: You allude in your liner notes to final changes Herrmann made in the score at the time of recording. Can you tell us what some of those changes were and why he made them?

Morgan: There are a few instances where Herrmann changed an instrument here or there, probably because of interference with dialog or sound effects. In these cases (where we felt the changes were made to accommodate the film), we deferred to Herrmann’s original; however, if we felt he made the changes to better the music, we made the changes. It is impossible to get into Herrmann’s head now, so each time we had to make the call solely on musical considerations and our own perceptions.

KL: Compare your version of the score to Herrmann’s version. Aside from better sound quality and the restored cues, what are the main differences in approach? How would you describe William Stromberg as a conductor?

Morgan: Although Bill is very loyal to the music and the original performance, he is also aware that this is a performance of the music away from the film and certain awkward tempos to catch some point in the film can be avoided. Some things Bill took faster, like the SIESTA cue that I feel makes the music work better as music. I remember an interview with Herrmann where he said he hated original soundtrack performances because he was always aware of the conductor “catching” things. I think Bill’s interpretation is a legitimate interpretation of the music. Nothing is really out of whack when compared to the original. I think the Moscow Symphony with Bill conducting did the music complete justice.

KL: Like many of Herrmann’s works, Garden of Evil‘s score centers around what Christopher Husted calls “a brief, arresting figure.” Any comments on how Herrmann’s film music generally depends more on texture (“mosaic forms”) than on long, developed melodies?

Morgan: Of course, this is what Herrmann is all about. His music is often just plain mesmerizing or hypnotic when he cleverly uses this texture. Then too, this is why some people find his music to be repetitive or underdeveloped. The point is, it is great film music and assists the drama perfectly. In an interview Steve Smith had with Robert Wise, Wise commented on Herrmann’s cooperation when music had to be cut at the last minute for editing changes, and how composers like Max Steiner would fight and complain about how it would ruin the music and he would have to rewrite it for the new timings. Well, what needs to be added here is Herrmann’s music is much easier to edit by adding or subtracting his musical “cells”. Steiner worked with more melodic and linear music that just couldn’t work by simply removing a few bars here and there. If one ever has the chance to look at Herrmann’s Journey to the Center of the Earth score and follow it with the music as recorded, it seems that every other bar has been eliminated in the final film.

KL: Husted also calls Garden of Evil “a remarkable achievement in orchestration.” What is most impressive to you about Herrmann’s orchestration here?

Morgan: His clarity. Although Herrmann loves doubling many instruments on a line, the lines are always very clear and concise. Herrmann’s real talent is primarily in his orchestrational abilities. Take a nonthematic related cue from one of Herrmann’s scores and play it on the piano. I bet the casual listener would have difficulty in distinguishing one cue from another, but with the orchestration attached, the music comes alive and becomes very distinctive to that particular score.

Conductor Bill Stromberg and myself were discussing performing Herrmann a few weeks ago and we both agreed that one of primary considerations in performing Herrmann is to make sure all accents, phrasing and dynamics are carefully adhered to, even exaggerated. Because Herrmann’s music is so symmetrical, it usually goes down on tape fairly easily, but all orchestras tend to be lazy when reading heavily annotated parts and it is up to the conductor to make sure the orchestra stays on its toes.

KL: Talk about the special instructions in the score to produce a “wind harmonic” to match the desert ambience of the story. Was this easy to reproduce in your version?

Morgan: This is an avant-garde effect that produces weird, wind-like harmonics that can create an eerie calm in the music. It is a subtle effect, but haunting. Once the method is explained to the brass players, it is easily produced. Although they are “fingering” notes with their valves, they are only blowing air through their instrument, thus giving the “wind” sound that is actually a “note” or tone.

KL: Steven C. Smith’s liner notes describe Herrmann’s Prince of Players overture as “unique in his film work.” How so?

Morgan: The Prelude really has a marvelous way of introducing us to the world of stage. It is very symmetrical music, but has a somewhat English flavor reminiscent of composers such as Walton, Elgar and Bliss. You could certainly imagine this type of score being composed for one of Laurence Olivier’s Shakespeare films.

KL: Do you see any parallels between Herrmann’s portrayal of psychological disturbance in this film and in, say, the earlier Hangover Square or the later Psycho?

Morgan: Not really. I think this score is closer to his other “adventure” scores in terms of dramatics and thematic manipulation. It firmly belongs to his mid-fifties Fox period where stereo sound inspired him to compose large scale scores with colorful orchestrations.

KL: As you note, the orchestra on Prince of Players is “atypically, a conventional one,” except for an organ and an expanded clarinet section. What are some of the unusual effects Herrmann wrings from this standard setup, and how does he do it (I’m thinking of the “chamber-size groupings” you mention)?

Morgan: Much of the music style of this score reminds me of some of the quieter passages in The Three Worlds of Gulliver. It definitely has a certain “English” simplicity to it. Many of the cues are scored for certain sections of the orchestra as opposed to tutti scoring. For the most part, it is very delicate music, reflecting the psychological makeup of the characters, but with that consistent “English” sound to remind you of the literary and stage world these characters inhabit.

KL: You speak in your notes of incorporating “all major themes and cues from the film.” Did space constraints force you to leave out anything you regretted?

Morgan: Well, I think our Suite is well-rounded and fulfilling as a piece of music. A lot of the music we didn’t do is more or less repetitious of what we did do. If we only did Garden of Evil, the disc would have been less than 60 minutes and so I decided to prepare a suite that incorporated all the major musical highlights of this score. I really feel we did this score complete justice, although I am sure some die-hard fans would have liked it complete. (Of course, if anyone does record it complete, I’ll buy it!)

KL: Would you care to address a discussion thread I know you’ve followed (and sometimes contributed to, with Mr. Stromberg) in the online movie music newsgroup–that is, the pros and cons of rerecording classic scores? Is it true that the original tracks for Garden of Evil are no longer in a usable state? What about Prince of Players?

Morgan: I believe these two scores have been transferred to DAT. I don’t know what survives or what quality

Prince of Players is in, but Nick Redman mentioned to me that not all of

Garden of Evil could be saved. The only con to a rerecording is if it’s lousy.

My feeling is any good music should and can hold up to different interpretations. Whenever you have a large orchestral score, it is impossible for all its subtleties to be displayed in one recording. I have several recordings of the same piece by many classical composers, and they all highlight or bring out something different in the music. I remember years ago, I would make up my own ideal Mahler Symphony #3 interpretation by combining movements from different orchestras and conductors! Sometimes a slower performance will lose some excitement, but gain in revealing inner-line details or colorations. I don’t care for some of Herrmann’s Phase 4 rerecordings of his music, but even with the slow tempos–for instance in the skeleton fight from Sinbad [The 7th Voyage of Sinbad]–one can notice two xylophones trading off between themselves and hear some wonderful orchestrational detail that just flies by when the piece is played up to speed.

Don’t get me wrong, I love the excitement of original soundtrack performances and will always look forward to their release. Any good performance is legitimate. Stravinsky and Copland were competent conductors and there is a sort of historical importance to their interpretations, but frankly, I enjoy other interpretations more. I enjoy Joel McNeely’s Vertigo rendition more than the original.

KL: Tell us about your future plans for other Herrmann-related or film-related projects. Is your new version of The Egyptian in the can yet? Anything else in the pipeline we should know about?

Morgan: The Egyptian is sort of in the can, but Bill and I have not heard the first-edits yet. I am sure he will be bringing these back from Moscow at the end of June. When we get the initial edits, Bill and I go through them and indicate places that we think they can find better replacements for. It usually takes a few edit sessions to get what we feel is the best. It is really tough, as we are doing what in fact are live mixes for this music. We record directly to two-track and the engineer has a score and I am in the booth pointing out what needs to come out, etc. Since the recording brings out details that Bill really can’t always hear in the recording hall, we must be on our toes in order to get the best possible balance.

KL: By my count, these are the Herrmann scores that have never had any official release of any kind (not even a suite or a single cue): Five Fingers, A Hatful of Rain, The Naked and the Dead, Blue Denim, Twisted Nerve, Endless Night, Obsessions (not to be confused with [de Palma's] Obsession). Do you have plans for any of these?

Morgan: Actually,

The Egyptian was a replacement for another Herrmann album I was preparing. Initially, we wanted to do the complete

Five Fingers (about 35 minutes of music) and fill out the album with 35 minutes from

The Snows of Kilimanjaro. We then found out a bigger company wanted to do Herrmann and those titles were among the titles they wanted to do, so we were denied access to the materials.

The Egyptian was a very complicated score to do. The original recording of

The Egyptian had the chorus as an overdub, but we had to do it live, with the orchestra. This created balance problems. We hope we solved them! There were a lot of strange overdubs and special recording manipulations on this score we had to overcome and try to get the same effect live.

Bill and I very much would like to do some of The Naked and the Dead, as well as music from The Battle of Neretva, which has a ton of music that didn’t make it into the film or onto the soundtrack album. The film was heavily cut, so I don’t know if it was even recorded. I am kind of leery about naming titles this early, as I am sure some bigger company would think: “What a great idea! Let’s do it ourselves.”

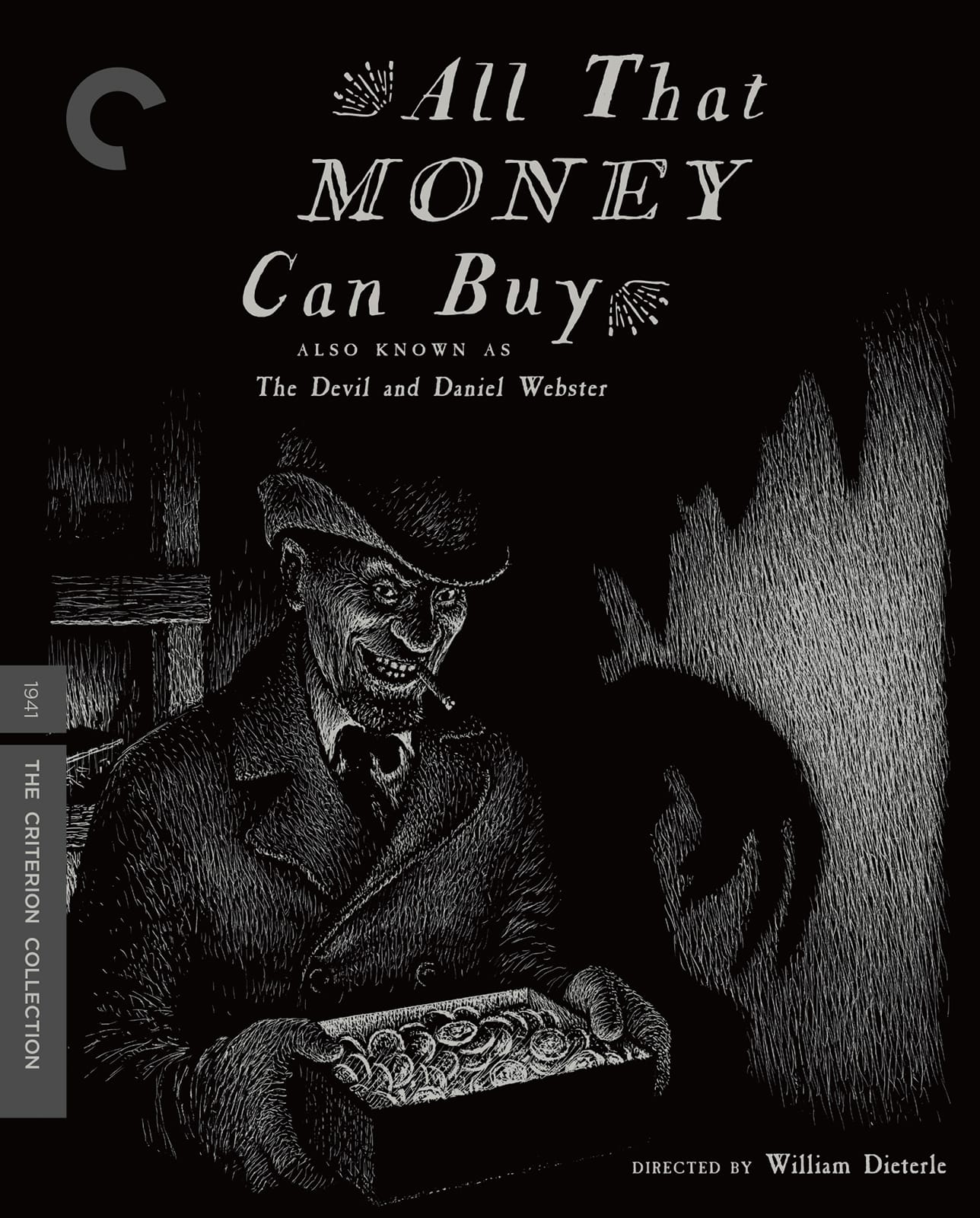

KL: And the following Herrmann scores have only had portions released or rerecorded: The Devil and Daniel Webster, Hangover Square, Anna and the King of Siam, On Dangerous Ground, The Snows of Kilimanjaro, White Witch Doctor, Beneath the 12-Mile Reef, King of the Khyber Rifles, The Kentuckian, The Trouble with Harry, The Man in the Gray Flannel Suit, The Man Who Knew Too Much, The Wrong Man, Tender is the Night, Marnie, Fahrenheit 451, The Bride Wore Black.

Morgan: These are some great scores you have mentioned. I still think there is a chance for Marnie in stereo to be released from the original music tracks. Some of the Fox titles I am sure will come out eventually. I don’t think Universal has any stereo tracks to Fahrenheit 451, so someday I would love to do a complete rerecording. There is a fair amount of music that didn’t make it into the final film.

KL: When you add all of his radio and TV stuff (e.g., the pilot for The Virginian that was on a vinyl boot years ago) and such specials as A Christmas Carol and A Child is Born, you realize there is still a wealth of Herrmann material waiting to be unleashed on the world. Any other obscure favorites you’re hoping will come out someday?

Morgan: I wish someone would do a new recording of Herrmann’s Moby Dick. It would best be done in England, but it is my favorite nonfilm work of his and deserves a first-rate recording with great singers.

KL: Any final words for all of those rabid Herrmann fans out there?

Morgan: We certainly live in a great era for classic film music on CD. There has been a sort of Renaissance of classic film music in the last several years, both original and re-recordings. Some good, some bad, but it is a good sign. Doing these recordings is very expensive. Frankly, all the Herrmann and film music buffs combined can’t buy enough discs to make these things commercial. We must reach out to connect with other audiences. We at Marco Polo have crossed over to the classical market, and in some instances, general film buffs that may not normally buy soundtracks. That is why my main concern is the music itself–does it work as music away from the film? It comes down to, is it good music, not is it good film music.

![The Man Who Knew Too Much – 4K restoration / Blu-ray [A]](http://www.bernardherrmann.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/TMWKTM-4K.jpeg)

![The Bride Wore Black / Blu-ray [B]](http://www.bernardherrmann.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/07/BrideWoreBlack.jpeg)

![Alfred Hitchcock Classics Collection / Blu-ray [A,B]](http://www.bernardherrmann.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/AHClassics1.jpg)

![Endless Night (US Blu-ray) / Blu-ray [A]](http://www.bernardherrmann.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/EndlessNightUS.jpg)

![Endless Night (UK Blu-ray) / Blu-ray [B]](http://www.bernardherrmann.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/12/ENightBluRay.jpg)