‘I count myself an individual. I hate all cults, fads and circles.

I believe that only music that springs out of genuine personal

emotion and inspiration is alive and important.’

Brooding, loud, dark, intense, oppressive, thoughtful and subject to sudden mood swings. This description might be seen to describe both the music and personality of one of the greatest composers of the twentieth century, Bernard Herrmann.

Although he composed a large body of orchestral, television, theatre and radio work, American born Bernard Herrmann — Benny to his friends — is principally remembered for his many fine film scores. His appeal to film fans — especially horror and fantasy buffs — has, if anything, increased since his death in 1975. With a wealth of recently reissued scores, not to mention many recorded for the first time, there’s never been a better time than now to start collecting his work.

Herrmann wrote film scores for a veritable who’s who of famous (and sometimes infamous) movies. From his first scoring success with Citizen Kane to the memorably chilling scores for Psycho, Sisters and Taxi Driver, his music is consistently dramatic and exciting. Alongside thrillers and mainstream pictures, Herrmann also wrote music for a number of excellent fantasy and science fiction movies, which include the stop motion FX films of Ray Harryhausen, and SF classics such as The Day The Earth Stood Still, Fahrenheit 451 and Journey to the Centre of the Earth. Common to them all and fundamental to the enhancing of the visual image is Herrmann’s sweeping, poignant, often ominous but always dramatic musical accompaniment.

A common assertion among film fans is that film music is principally background music and does not deserve to be heard away from the film. Certainly there’s a strong argument for this; some film music, including the scores of Bernard Herrmann, don’t take well to being isolated, often because they’re too bleak and depressing to listen to divorced from the celluloid image (examples of Herrmann scores where this is the case include the consistently forbidding music for Psycho, Cape Fear and It’s Alive). However, Herrmann’s great strength was to compose music which was integral to the film experience, both sharpening its focus and elevating the visuals to new heights whilst, for the most part, avoiding the trap of writing music which overwhelmed the film it was intended to complement.

Bernard Herrmann was part of the so-called ‘Golden Age’ of film composers — though it was a term he loathed. He saw himself first and foremost as a composer who sometimes wrote music for films, a period which originated in the 30s and 40s and whose adherents included the likes of Alfred Newman, Franz Waxman, Erich Wolfgang Korngold, Max Steiner and Miklós Rósza. Where Herrmann differed was in his approach to composition. His was music of the emotions — often the darkest and most intense of emotions. Instead of writing music which used specific motifs to comment on the action Herrmann was the first to use music which expressed the emotional fluctuation of the characters. Whereas composers like Max Steiner, whose excellent scores include the 1933 version of King Kong and Gone With the Wind, used an intellectual approach to scoring — where, for example, the villain is announced with stereotypical ‘villain music’ or where the image of a British warship might be accompanied by a segment of ‘Rule Brittania’ — Herrmann’s was a passionate response: music that commented on the interior psychology of a character in a scene.

Until the appearance of these composers films were scored using uncopyrighted works of the masters, from which snippets were taken before being sandwiched on to the soundtrack. In the early days of Hollywood composers hailed from Tin Pan Alley, Broadway and vaudeville. Many of these weren’t really composers at all but songwriters restricted by the limited musical vocabulary of 20th century pop music. This resulted in light, overly romanticised music — music which studio heads regarded as a saleable commodity and which led to a conveyor-belt mentality with composers allowed little or no time to come up with challenging new scores. It took someone like Bernard Herrmann, whose background was Carnegie Hall not Broadway, to lend film music intelligence and sophistication and help elevate it to the status of art.

Today a number of strong partnerships exist between directors and composers. For example: Steven Spielberg and John Williams; David Cronenburg and Howard Shore; Tim Burton and Danny Elfman. However, the partnerships forged between Herrmann and the directors/filmmakers he collaborated with are nothing less than the stuff of legend: Alfred Hitchcock, Orson Welles, Ray Harryhausen, Brian De Palma and François Truffaut are just some of the famous personages he worked with during his tumultuous career.

Bernard Herrmann was born in New York on June 29, 1911, of a non-musical family. His birth name was actually Max Herman (which his father Abram may have chosen in honour of a close friend, Max Robin). After bringing his son home from the hospital Abram decided not to call him Max after all, and chose Bernard instead. Bernard hated the name Max and his family frequently teased him in his youth. (In an interesting aside, there was a British composer called Bernard Herrmann, a fact which caused nothing but consternation for the American Herrmann who used to receive the latter’s fan mail on a regular basis while living in England!)

Herrmann’s father might well have been the catalyst for his son’s interest in music. As well as taking both Benny and his younger brother Louis to operas and symphonies, and giving each a musical instrument to play from an early age (in Benny’s case, a violin), Abram’s tales of whaling voyages and wrecks at sea can’t failed to have fired his eldest son’s imagination. Indeed, Herrmann was later to write a cantata called Moby Dick (partly the result of reading Melville’s novel); whilst many of his scores — such as Anna & The King of Siam, White Witch Doctor and fantasy scores like The 7th Voyage of Sinbad and Mysterious Island — utilise exotic scales and ideas to suggest faraway locations.

The young Herrmann took music lessons at school and at the age of twelve won a prize for a self-composed song. By the time he was thirteen he had discovered Hector Berlioz’s Treatise on Orchestra, a book which the composer later credited as the impetus for his future career. His musical education continued at New York University where he studied composition, and as a fellowship student at the Julliard School of music. By the age of eighteen he was conducting his own orchestra, giving concerts of works by lesser known composers — something he would continue to do right up until his death. Whilst his violin playing was hardly inspired, and with a singing voice which made would have made a dog cringe, Herrmann nevertheless concentrated on developing his piano playing and becoming a good conductor.

His first major success was in being hired by the Columbia Broadcasting System in 1934 for whom he wrote incidental music to accompany their educational programmes and where he was employed as a conductor of the CBS Symphony Orchestra. This lead to his being asked to write music for radio drama, a role he made his own, composing music that transformed an essentially static medium into something worthy of attention. It was through his association with radio that he met and befriended the youthful Orson Welles, scoring a number of his broadcasts, including the now infamous adaptation of H.G. Wells’ The War of the Worlds (for the Mercury Theater on the Air in 1938), which resulted in nation-wide pandemonium due to the audience’s belief that Martians had actually landed and were about to take over earth!

However, it was his friendship with Welles that was directly responsible for his most lucrative work to date. When in 1939 Welles requested that Herrmann accompany him to Hollywood to score his first and most famous picture, Citizen Kane, the young composer was only too happy to agree. When his next score, for 1941′s All That Money Can Buy (aka The Devil & Daniel Webster), won an Academy Award, his future seemed assured.

To assess Herrmann’s success in the film world it is first necessary to understand the composer himself. Herrmann was a complex man whose perceived weaknesses — his explosive temper and intolerance of sub-standard musicianship, to name but two — often worked for rather than against him. Here was an outspoken, highly literate and intelligent man whose intense interest in film and the dramatic medium allowed him to write music rich in musical colour; and which, when carefully placed under a dialogue track, increased the import of the spoken word, lending dialogue a greater significance than it might otherwise have had.

Herrmann came from an era of ‘serious’ composers. He was still a young man when the Depression hit hard in America in the 30s; the rise of Nazism can’t failed to have affected the way he perceived people and their motives being himself of Jewish parentage. Consequently his film music has a distinctive weight and intensity often lacking in today’s scores.

Like the man himself, many of Herrmann’s most memorable scores are brooding and portentous in nature. Even the purportedly romantic music for films like Jane Eyre and The Ghost and Mrs Muir has an edginess and a sense of nostalgia and sadness which perfectly complement the films in question. As one critic observed, his was the music of ‘Gothic and gas light’.

Much has been written about Herrmann’s irascibility, his seemingly unprovoked rages and outrageous and opinionated views of others. Both his father and his grandfather shared his temperament, which at its worst led to a reddening of the face, a tensing of the facial muscles and a string of curses and insults — all apparently unprovoked.

Herrmann was distrustful and intolerant of the musical opinions of others. To one unfortunate recipient he retorted: ‘Your views are as narrow as your tie’. Another instance can be found in the reminiscences of actor, producer and director, the late Paul Stewart (who starred as the sinister valet in Citizen Kane and consequently knew both Welles and Herrmann). His first contact with the composer came when he was hired to produce Welles’ Mercury Theater on the Air. Recalls Stewart:

I immediately found him extraordinarily eccentric and irritable. He had very little interest in me, as he did in very few other people. I don’t think he knew he was unfriendly, but he just was. [2]

Another occasion, the scoring session for the infamous The War of the Worlds, saw the two come into conflict — with amusing results:

Benny was a classical conductor … to get Benny to do songs {the radio broadcast required the orchestra to simulate a dance band program, which is interrupted by bulletins about the Martian invasion} that I suggested was almost an impossibility. He didn’t understand the rhythms or anything…. I remember saying to him, “Benny, it’s gotta be a beat like this…” {snapping fingers} and he got very upset. He handed me the baton and said, “YOU conduct it!” So I got up on his little podium, the musicians looked at me … they all understood his personality, so when I gave the downbeat, they played it just the way I wanted it! … I handed the baton back to Benny, and he was crestfallen. You know, I don’t think I ever saw Benny happy. He always seemed impatient, and it was his impatience and apparent lack of humour that made him the butt of many jokes by Welles … he was teased a lot to show this side of his personality. The orchestra did it more than anybody; they were so pleased that time I took his baton. …I don’t think (Benny) knew how to get along with people. Everybody admired him, but they found him difficult — which is true of all artists… [3]

As well as possessing a gruff and difficult personality, Herrmann was highly intolerant of dictation from producers and directors who lacked musical knowledge. To Herrmann all motion picture music (apart from his) was ‘a bunch of junk’. It was an attitude that would lose him a great deal of commissions — not to mention friends — throughout his career.

Yet the question remains: Would Herrmann’s music be half as powerful were it not for the influence of his daunting personality? As Herrmann’s great nephew (and sometime Herrmann Genealogist) Steve E. Rivkin suggests, ‘…these personality traits that people have looked on as flaws helped to make him the great composer that he became. Strong opinions, argumentative, belief in himself, belief in his music, made him wage war with any who didn’t see it his way.’ [4]

It was almost entirely due to the confidence that Welles had in Herrmann that resulted in his move to Hollywood and their resulting partnership. Herrmann’s first score, Citizen Kane, the story of the spectacular rise and fall of self-styled newspaper tycoon, Kane, was a highly successful combination of traditional Americana themes and ideas (Herrmann’s association with American composer Aaron Copland and his ilk would result in several scores rich in the musical tapestry of American folk music). His work for radio — for which he composed, arranged and conducted over 1,200 programmes — had developed Herrmann’s ability to write music which complemented mood and character, themes Welles was trying to make explicit with his images and dialogue.

Herrmann’s score was a complete success. The eerie opening featuring flutes, contrabass, clarinets, tubas, trombones, low percussion and vibraphone later gives way to the lively tempos which accompany the growth of Kane’s first newspaper; and later still to Neo-Romantic mood music that lends parts of the film an undeniable sombreness. Herrmann achieved this effect by utilising bass clarinets, low trombones and tuba, an instrumental combination which leant a dark tone to this and other of his movies, a technique much emulated nowadays. Kane was also unique in that Herrmann rejected the then-popular Hollywood practice of scoring a film with almost non-stop music.

Welles was over the moon with Herrmann’s score. Indeed many years later he would state that Herrmann was ‘Fifty percent responsible’ for the success of his first movie.

Herrmann’s next film score was for All That Money Can Buy (1941), the RKO debut of director William Dieterle which Herrmann completed just months after Citizen Kane. It was another score rich in Americana. Originally to have been called The Devil and Daniel Webster (the title was changed because of the box office failure of a previous picture, The Devil and Miss Jones — having ‘Devil’ in the title was perceived as being bad for business), the film again allowed Herrmann to experiment with simplistic but effective orchestration. Sleighbells clang, kettle drums signal a chase sequence, waltzes — such as the one where Miser Stevens is waltzed to death and transformed into a moth — twist and turn, becoming as dizzying to the viewer as to the characters onscreen.

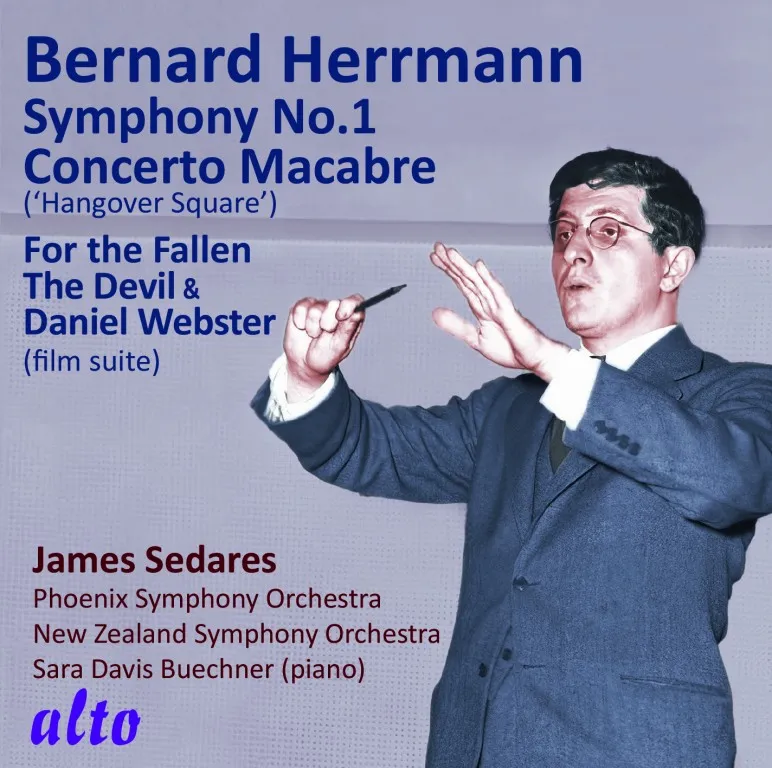

Such was the power of Herrmann’s score that he was to win an Academy Award, beating his own Citizen Kane score which was also nominated. As one of his more light-hearted scores it is still worth hearing today, and can best be experienced by tracking down The Devil and Daniel Webster Suite which Herrmann completed and premiered on CBS Radio in 1942.

With the exception of his score for Welles’ second feature, The Magnificent Ambersons (for which he refused to take credit due to extensive film editing), Herrmann’s 40s pictures successfully blended intriguing orchestral ideas with dramatic musical statements resulting in several fine scores. His score for Jane Eyre, for example — once again reuniting him with Welles, this time as actor, not director — utilised his by now trademark romanticism, at all times kept in check by the music’s dark colours, especially prevalent when Mr Rochester (played by Welles) appears on screen. (Interestingly, much of the music for Jane Eyre was culled from music Herrmann originally used for an earlier radio broadcast of Daphne Du Maurier’s Rebecca. The habit of reusing elements of his own work was something Herrmann would repeat throughout his career.)

Herrmann’s score for Hangover Square, on the other hand, is typical of the dark mind states he loved to explore. The film starred actor Laird Cregar as demented composer, George Bone whose occasional spells of amnesia leads to bouts of brutal murder. It’s Bone’s intention to write a piano concerto, and his fractured thought processes are brilliantly captured by Herrmann when, during the finale, he plays the completed piece (which Herrmann later recorded as Concert Macabre for Piano and Orchestra) whilst the house burns down around him, the music depicting Bone’s seething madness to perfection.

Hangover Square also allowed Herrmann to explore one of his favourite themes: obsession. Later efforts would target characters that were driven by some psychological complex — whether these be Taxi Driver‘s Travis Bickle, Hitchcock’s Marnie (from the film of the same name), Vertigo‘s Scotty Ferguson or Obsession‘s Cliff Robertson. It was a theme that would produce some of the composer’s most powerful music.

Two other notable scores Herrmann composed in the 40s were for (the Academy nominated) Anna and the King of Siam and The Ghost and Mrs Muir. For the former, Herrmann used Siamese and Balinese music and set it in a western symphonic context.

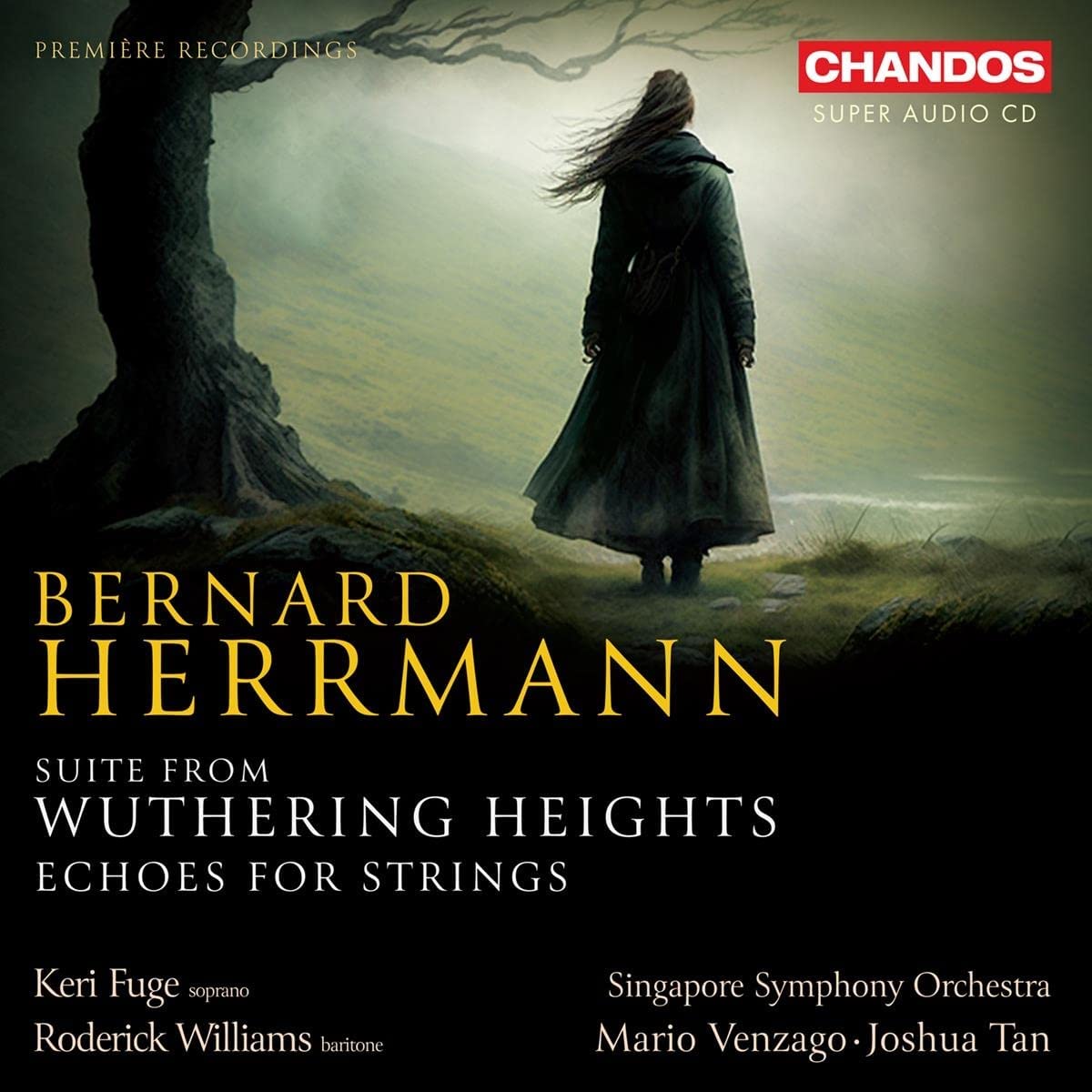

But it was Herrmann’s music for The Ghost and Mrs Muir, the tale of a lonely woman’s doomed love affair with the ghost of a long dead sea captain, that was to become his personal favourite. It also provided the perfect opportunity for Herrmann to apply his flair for gothic-romanticism to a story set in England, a place much beloved by the composer. His interest in gothic horror is used to good effect in this film, although its themes and concerns are more closely allied to melodrama than the conventions of horror or fantasy. As in Jane Eyre, Herrmann reflects the film’s tragi-romantic themes by using straightforward melodic ideas, resulting in a more traditional score — much of which ended up in his opera Wuthering Heights.

The 1951 SF classic, The Day The Earth Stood Still, on the other hand, is typical of the way Herrmann used unusual orchestrations to instil a sense of menace and other-worldly atmosphere. One of the first major science fiction films of its day, the score, like the movie itself, was way ahead of its time. By using underused instruments such as the theramin he suggested electronic music without using any electronic instruments.

However, a meeting with the film’s director Robert Wise a year later yielded a typical Herrmann response. After telling the composer about his next film, a semidocumentary called The Captive City, Hermann became intrigued enough to consider writing the music for it. Knowing that he didn’t have the budget to hire Herrmann Wise reluctantly agreed a meeting — with predictable results…

Bernie came and kept making his pitch until he finally said, ‘Well how much money do ya have in the music budget?’ ‘Bernie,’ I said, ‘We have ten thousand dollars.’ He hit the ceiling. ‘TEN THOUSAND DOLLARS?! HOW CAN YOU BELITTLE THE MUSIC WITH THAT KINDA THING?!’ He frothed at the mouth for ten minutes and stormed out. That was so typical; he was so insulted — not personally, but that that’s all we had for the score. [5]

The decade 1951-1961 would be Herrmann’s most creative and financially successful period. As well as scoring a number of interesting mainstream films like On Dangerous Ground, The Snows of Kilimanjaro, The Kentuckian (his only other movie western score being for Garden of Evil) and Prince of Players, it was also the period which would see the beginnings of Herrmann’s most auspicious partnership yet — the Hitchcock/Herrmann collaboration.

It seemed a match made in heaven. The quintessentially British director, a man of dry wit and a perfectionist in his art. And the American-born composer, a staunch Anglophile, well versed in English literature and an expert in English garden architecture, as serious about creating music as Hitchcock was about the art of film-making. (It wasn’t the first time they had met however, having been in touch with each other on several occasions during the 40s, with Hitchcock going so far as to request Herrmann’s services on his 1945 feature Spellbound {Miklós Rósza went on to score the picture instead.})

Many of the themes in Hitchcock’s movies must have greatly appealed to Herrmann’s own personality. The complex dichotomies of reality/fantasy, attraction/repulsion and obsession/detachment were concepts ideally suited to the composer’s music. Beginning with The Trouble With Harry in 1955 and ending with Torn Curtain in 1966 the Hitchcock/Herrmann scores are without fail some of the most inventive ever used in film.

Whilst Herrmann’s music for Hitchcock’s The Trouble With Harry and The Man Who Knew Too Much (in which the composer ‘does a Hitchcock’ by making his only film cameo, conducting the London Symphony Orchestra at London’s Royal Albert Hall playing Arthur Benjamin’s Storm Clouds cantata — used in Hitchcock’s original version of the film) contains a wealth of rousing and delightful musical ideas, it was his score for Hitchcock’s 1958 classic Vertigo that would take film music to new heights.

James Stewart plays Scottie, a policeman whose fear of heights prevented him from saving his former love, Madeline when she fell to her death from a bell tower; and whose obsession with the uncannily similar Judy eventually leads to an unavoidable tragedy. Herrmann composed Vertigo between January 3 and February 19, 1958. Unfortunately, a musicians’ strike meant that instead of being recorded in America, it was necessary to record in Vienna using the services of Englishman Muir Mathieson — whose conducting Herrmann later accused of being substandard. Nevertheless, it remains one of Herrmann’s most widely discussed scores, the recent 1996 re-recording (conducted by Joe McNeely) being as fine an example as any of the emotional depths plumbed by Herrmann’s haunting, pseudo-romantic music.

Herrmann’s opening prelude, accompanied by Saul Bass’s swirling images, conjures perfectly the spiralling vortex into which Scottie is plunged as he desperately searches for ways to assuage his guilt-ridden conscience. As in the best film music, Herrmann’s suspenseful prelude draws the viewer closer to the celluloid image, telling him: keep watching, this is serious, something bad‘s going to happen.

To create a feeling of unease in the opening titles, Herrmann wrote a melody that had no obvious resolution. Twentieth century audiences used to hearing tonal music — often incorporating major and minor thirds, such as the introduction to Beethoven’s 5th Symphony — are likely to be immediately put off balance by Herrmann’s habit of using thirds in a parallel series of notes. Thus the music appears to turn in on itself, resulting in unease on the part of the viewer. Herrmann was to use this technique again and again with great success in his films — for instance, in the opening to Sisters and as an obsessive and repetitive litany throughout Psycho

It’s a mark of Hitchcock’s trust in his composer’s abilities that Vertigo contains more music than spoken dialogue. Here was a film where the director’s neuroses and sense of drama were matched note-for-note by his composer’s atmospheric music. Where the dramatics and melodramatics of the score heightened the sadness and aching nostalgia of Scottie’s fractured personality. For the five minute ‘Scene D’Amour’ cue, where Judy is finally transformed in to an almost exact replica of Madeline, Hitchcock allowed almost no dialogue, saying to Herrmann, ‘We’ll just have the camera and you.’ As a result, the music becomes almost the ‘third character’ in the scene.

Herrmann’s next Hitchcock score was for the Cary Grant vehicle, North by Northwest. Essentially a ‘mistaken identity’ adventure yarn, initially set in New York, Herrmann, in typical fashion, chose not to use ‘city music’ but instead composed a fandango, a Spanish dance, which, amongst other instruments, used tambourines to accompany the action-packed sequences. Starting with a flourish and climaxing in brutal fashion, Herrmann’s score makes use of all his trademark techniques, including repeating small snatches of sound over and over, the brash melodies and tumbling tempos combining to hammer the senses into exhausted submission.

However, it was Herrmann’s next score for Hitchcock, Psycho, that would help cement both the director and the composer’s reputations. Absconding thief, Marion Crane (Janet Leigh) is brutally murdered whilst staying at the Bates motel, apparently at the hands of its proprietor’s (Norman Bates) crazy mother. However, when the investigation begins it soon becomes evident that there’s a lot more to Norman than meets the eye…

Psycho was a horror flick through and through, using monochrome images to reinforce its director’s gothic aspirations. Writing on a small budget, Herrmann’s score used only a string orchestra ‘to complement the black-and-white photography of the film with a black-and-white score.’ [6] As in Vertigo, with Psycho Hitchcock wanted Herrmann to score lengthy, dialogue-free scenes so that the audience was made aware it was being led towards a dreadful revelation. In 1973 Herrmann commented:

I wrote the main title to Psycho before Saul Bass even did the animation…. After the main title, nothing much happens for 20 minutes or so. Appearances, of course, are deceiving, for in fact the drama starts immediately with the titles…. I am firmly convinced, and so is Hitchcock, that after the main titles you know something terrible must happen. The main title sequence tells you so, and that is its function: to set the drama. You don’t need cymbal crashes or records that never sell.’ [7]

For the infamous shower sequence — where Crane is stabbed to death whilst taking a shower — Hitchcock originally wanted no music, a decision that Herrmann ignored, going on to write one of the most chilling film music accompaniments ever devised. This jarring and shocking music — which had its origins in the composer’s 1935 concert piece, Sinfonietta for String Orchestra — utilised pitched violins to produce shrill, bird-like shrieks, a technique which cleverly announces the identity of the killer, whose hobby happens to include stuffing birds.

Herrmann also provided memorable — if self-referential — music to Hitchcock’s Marnie, and acted as sound FX supervisor on The Birds, which had no music. However, his working relationship with Hitchcock was to come to a spectacular end when he was asked to score Hitchcock’s ill-fated Torn Curtain. Around this time the use of jazz and pop music in film scores was becoming prevalent in Hollywood. Herrmann, who had always detested their use, reluctantly agreed to update his sound which in certain circles was now regarded as old fashioned. The result, a powerful set of orchestral cues, utilising the bizarre combination of sixteen french horns, twelve flutes, nine trombones, two tubas, two sets of timpani, eight cellos, eight basses, and a small group of violins and violas, was arresting enough to occasion a standing ovation from its orchestra, a rarity amongst session musicians. Hitchcock, however, was not amongst them.

A principal murder sequence (which again the director had wanted unscored) and at least half the score had been recorded before Hitchcock arrived at Goldwyn Studios in March 1966. Excitedly, Herrmann asked his engineer to play back his prelude to Hitchcock — whose response was anything but favourable. When then told that Herrmann had scored the murder sequence against his wishes, the curtain well and truly came down. After calling off the session (a big deal in those days), the two later exchanged heated words on the phone, a conversation in which Herrmann protested that he didn’t write pop music and if that was what he wanted, he should get someone who did. (The picture was rescored by John Addison.) It was the last conversation they would ever have, and a sad end to one of the most fruitful director/composer relationships in cinema history.

Thankfully there were happier collaborations for Herrmann. Prominent among these was his association with producer Charles Schneer whose fantasy films used the ingenious talents of stop motion FX artist, Ray Harryhausen. After some initial reluctance on the part of Herrmann, who had never scored a picture like it, he agreed to write the music for Harryhausen’s first colour fantasy, The 7th Voyage of Sinbad.

The result was one of Herrmann’s most Arabesque and symphonic scores. In the words of the composer:

I worked with a conventional sized orchestra, augmented by a large percussion section…. By characterising the various creatures with unusual instrument combinations … and by composing motifs for all the major characters and actions, I feel I was able to develop the entire movie in a shroud of mystical innocence. [8]

The ‘creatures’ make reference to Harryhausen’s outlandish and strikingly animated creations, which include a dragon (signalled by timpani and bass), a cyclops (loud timpani and the crash of cymbals), a two-headed bird called the Roc (wind, bells and harp) and a reanimated skeleton, for which the composer used the xylophone to suggest ‘bone music’. Indeed this sequence (named ‘The duel with the skeleton’), in which Sinbad does battle with a skeleton, is one of the film’s most enduring musical moments, a series of clacking percussion that sounds as though its creator was playing on a stockpile of bones!

Until now, Harryhausen’s fantasies had used standard studio scores as limiting as the black and white film medium they were filmed in. For The 7th Voyage of Sinbad, however, director Nathan Juran incorporated the mythical world of the Arabian Nights. The accompanying score is rich in orchestral colour, lending the film a sense of the exotic and from the opening scene infusing the visuals with a sense of potential danger.

Further evidence of his mastery of the orchestral environment is evident in his next Schneer score, The 3 Worlds of Gulliver. Based on Jonathan Swift’s satirical novel, Gulliver’s Travels, it allowed Herrmann, who himself now lived in London, to evoke the glories of Eighteenth Century England through period pastiche. Each of the three worlds is allocated a ‘sound’ that immediately identifies the setting. England, for example, is evoked with pompous brass; celesta and sleighbells becomes the theme of the tiny Lilliputians; whilst the giant Brobdingnagians are announced with tuba, contrabassoon and bass.

As in The 7th Voyage of Sinbad, Herrmann’s careful choice of instruments to represent the sizes and temperaments of the various creatures increases the viewer’s willingness to accept the impossible, the ultimate aim of any filmmaker.

For his next Harryhausen collaboration — a loose sequel to Jules Verne’s 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea called Mysterious Island — Herrmann again utilised a large but conventional orchestra to characterise the island’s many outlandish creatures, which included gigantic birds, crabs and bees. For the ‘The Giant Crab’ sequence Herrmann, in typically bombastic fashion, combined horns, wind and strings to induce the sounds of battle (something he was especially good at: see his scores for the military epic, The Battle of Neretva and the mythological Jason and the Argonauts). Similarly, the ‘The Giant Bees’ cue makes intriguing use of the brass section to convey a sense of an otherworldly battle between the human protagonists and the enormous flying insects.

The alliance between Herrmann and Schneer was by now becoming quite strained. Herrmann’s bullying and his disputes over money had once again taken its toll on a working relationship. As such, Herrmann was to score only one other picture for Schneer.

Jason and the Argonauts, arguably the most effective of Harryhausen’s stop motion epics, adapts the Greek myth of Jason and the Golden Fleece, a tale of heroism and adventure and the perfect venture for FX man and composer alike. Conjuring the mystique of ancient Greece is no easy task, but Herrmann rose to the challenge with typically boisterous results. Using only brass, woodwind and percussion, Herrmann’s music immediately grabs the viewer’s attention, from the title sequence’s triumphant battle march, to the subtly ominous opening. The sequence where the giant bronze man, Talos, stalks his island’s unwelcome visitors is typical of the way Herrmann makes music integral to the viewing experience. By limiting the orchestra to three sections he manages to suggest the sheer size of his adversary, the music coating Talos in a militaristic sheen as reflective as the bronze from which he is formed.

The Harryhausen epics weren’t the only fantasy films Herrmann worked on in the Fifties and Sixties. Two others, Journey to the Centre of the Earth and Fahrenheit 451, showcased his unerring ability to lend life to a fantastical premise. In the former, Herrmann again experimented with instrumental combinations, his string-less orchestra consisting of brass, wind, harps, percussion, cathedral organ, four electric organs and an archaic instrument called the serpent. The non-melodic sounds invoked by this unusual blending of instruments make for some of the most unearthly music ever to accompany a film; the ‘Atlantis’ cue, a series of low register organ chords, plus vibraphone, being particularly memorable.

However, it was his score for François Truffaut’s film adaptation of Ray Bradbury’s Fahrenheit 451 that would showcase some of his most beautiful and nostalgic music. Set in the distant future, the novel tells of a society where books have been outlawed, and which are burned, Nazi-style, by firemen employed for the purpose. In order to express the book’s aching nostalgia — rendered curiously sterile by Truffaut — Herrmann chose the traditionally Romantic combination of harps, strings and percussion, a direct contradiction of Truffaut’s assertion that he should use futuristic music to summon up a futuristic society. The film was a failure, but its director was courteous enough to send Herrmann a note saying, ‘Thank you for humanising my picture.’

After the Torn Curtain fiasco, Herrmann and his music become somewhat unpopular in Hollywood. A staunch Anglophile, he made the decision to move with his third wife, Norma, to Chester Close in North London, the former residence of Christine Keeler (whose involvement in the Profumo sex-scandal ensured Keeler instant infamy in the Sixties).

During the last five years of his life he would once again find his services required by a number of up-coming filmmakers. Such modern day masters as Brian De Palma, Larry Cohen and Martin Scorsese would go to great lengths to elicit his assistance on their pictures; resulting in some of the most triumphant scores of his career.

When engaged by De Palma to score his low-budget shocker, Sisters, Herrmann responded with a score every bit as impressive as the best of his early work. Though both music and the film it supported — the story of Siamese twins separated as children — were an all-round success, the usual composer/filmmaker tensions abounded. During a mixing session at New York’s Reeves Studio film editor, Paul Hirsch, was to experience the withering blast of a Herrmann retort:

…finally we got to the murder sequence, and the music mixer forgot to turn on Benny’s score…. (Benny) called out over his shoulder, ‘Where’s the music? Isn’t there music there, Paul?’ — addressing me. The mixer said, ‘No, I forgot to …’ All Benny heard was no. And since he was addressing me, he thought I was saying, ‘No, there’s no music there.’ He stood up and flew into a volcanic rage, screaming at me, ‘How DARE you tell me there’s no music there. I WROTE the music! I CONDUCTED it! I RECORDED it! You’re INSOLENT! Don’t you DARE speak to me that way! I’m going to report you to the union!’ And I had not said a word. [9]

Sisters was De Palma’s Hitchcock tribute, a suspenseful and at times quite scary film. Using a brooding, repetitive motif to suggest a school-yard taunt, the prelude sets the tone for the eerie visuals that follow. Herrmann used Moog synthesisers, glockenspiels and strings to invoke a pervading sense of gloom, which at times recalls Vertigo‘s air of mysterious detachment. Mirroring the scene in Psycho where Marion Crane drives at night to the Bates motel and her doom, in Sisters Herrmann scores a sequence where a female reporter drives to a mental hospital, the moody melodies symbolic of the impending danger she must face when later she is mistakenly incarcerated .

For Herrmann’s Obsession score, his second collaboration with De Palma -for which he also received a posthumous Academy nomination — Herrmann pulled out all the stops, utilising a choir and cathedral organ to create some of his most potent Gothic/Romantic music. As in Vertigo (of which Obsession is an inferior homage), some of Herrmann’s most moving music accompanies dialogue-free scenes, helping to reinforce the characters’ changing moods, moving the listener through the whole gamut of emotions, from joy (the beautiful ‘Valse Lente’ opening, echoed to devastating effect at the film’s finale) through hope, to, finally, despair.

Other directors were interested in securing the ageing composer’s services. For his 1974 horror flick, It’s Alive, the story of a deformed killer baby which commits grisly murders around Los Angeles, schlock-horror director, Larry Cohen hired Bernard Herrmann — after he had just turned down the opportunity to score William Freidkin’s The Exorcist. The spiralling insanity and bleakness of It’s Alive was ideal for Herrmann whose support for struggling filmmakers allowed him to be selective about the sort of subjects which interested him. By no means a great film, the score lends it a tension and dark wonder that the incredible plot badly needed. However, like his score for Psycho — which also lacked a string section — it is rather too joyless to listen to as music in its own right.

His last film score was for Martin Scorsese’s 1976 classic, Taxi Driver. As well as being a great film to bow out on — Herrmann died in his sleep hours after the final recording sessions had been completed — it was also the first time a Herrmann score had merged traditional orchestration with jazz — with impressive results.

Taxi Driver sees veteran actor Robert De Niro in the role of New York cab-driver, Travis Bickle, whose growing sense of isolation and paranoia leads to his declaring war on the city’s pimps and drug dealers. Scorsese’s brilliant study of festering hatred and man’s inhumanity to man was the ideal opportunity for Herrmann whose scores work best when seeking to illuminate the psychological complexity of human nature. Here his menacing music contrasts sharply with a lulling jazz theme — only partially composed by Herrmann — the rise and fall of the dramatic melodies occasionally softening into jazz to reveal a fragile, more human side to Bickle. Yet despite these more reflective moments, this is Herrmann’s most nihilistic score, its dark power best heard within the context of the movie.

Aside from the work he did on films, Herrmann composed for the concert environment, and his conducting duties resulted in a number of recordings, including The Planets by Gustav Holst, Great British Film Music (including compositions by Walton, Vaughan Williams, Lambert) as well as suites from own movies — often conducted at slower tempo than in the films.

He also contributed some memorable TV music, including the theme to popular series, The Twilight Zone, for which he composed several original scores; his scores for The Alfred Hitchcock Hour; and western series’ like The Virginian and Have Gun Will Travel.

As for his concert repertoire, Herrmann composed a body of interesting, at times innovative music which, though inferior to his film music, is still vibrant and moving and demands to be heard. Though only some of his concert works have been recorded, of those that have works such as his 1941 Symphony and his Echoes for String Quartet and Souvenirs de Voyage for Clarinet Quartet are well worth tracking down, if only to contrast the musical motifs he used in his films with those used in a concert environment.

Herrmann’s primary aim, however, was to become a great symphony conductor. Unfortunately, both his temper and irascible character would prove an immovable obstacle to the career advancement he so desperately sought. By alienating film personnel, musicians, and the orchestras he conducted, it was nobody’s fault but his own when he fell out of favour.

Yet Herrmann could be as generous as he could combative. On one occasion he recommended film composer, Elmer Bernstein — who would himself go on to conduct several of Herrmann’s most famous scores — for a film scoring job, at a time when work was hard to come by. He was quick to champion lesser known composers like Delius and Vaughan Williams, and one of the first to perform the music of Charles Ives, Aaron Copland and Cyril Scott.

Herrmann’s film music was characterised, not by easily-remembered melodies or catchy title cuts, but by music that drew the audience closer to the images onscreen; music that, in the composer’s own words, ‘…can invest a scene with terror, grandeur, gaiety or misery … propel narrative swiftly forward, or slow it down.’ [10]

When Herrmann started writing music for films he avoided the overly romantic scores of the time, preferring to foster an individual expression that concentrated on atmosphere, sounds and which stimulated the subconscious to react to the emotional turmoil of a fictional character. Though one might argue that film music is by definition the music of exaggerated emotions, and that much of it is only successful within the context of the film, truly great film music is that which works as great music in its own right.

In the words of producer/film composer, John Morgan: ‘…too often music is considered wallpaper rather than a creative element in movies.’ [11] Herrmann’s aim wasn’t to create ‘musical scenery’ however, but to ‘stimulate appreciation of, and … pride in life.’ Through his great erudition, his knowledge of the orchestra, and intimate understanding of the art of film-making, he helped elevate the film medium beyond mere budgetary restrictions. And in doing so, furnished the film music world with great passion and intensity — making made a bad film watchable, a good film great and a great film a life-enriching experience.

Notes

- Review of Herrmann’s London Phase 4 recordings by Royal S. Brown; Fanfare magazine; September/October 1996

- Interview with Paul Stewart, by Steven C. Smith (for A Heart at Fire’s Center: The Life and Music of Bernard Herrmann, published by University of California Press), conducted 1984 (The Bernard Herrmann Web Pages, p.1)

- Same interview, pp. 1/2

- ‘Benny, Max and Moby’ by Steve E. Rivkin, conducted March 1997 (The Bernard Herrmann Web Pages, p.2)

- A Heart at Fire’s Center: The Life and Music of Bernard Hermann (1991) by Steven C. Smith, p.166

- A Heart at Fire’s Center: The Life and Music of Bernard Herrmann, p.237

- A Heart at Fire’s Center: The Life and Music of Bernard Herrmann, p.238

- A Heart at Fire’s Center: The Life and Music of Bernard Herrmann, p.223

- A Heart at Fire’s Centre: The Life and Music of Bernard Herrmann, p.325

- Great Film Classics CD notes, p.6

- Interview with John Morgan, The Twelve Mile Reef: Bernard Herrmann On-line. p.1

With grateful thanks to Stephen Laws for his invaluable assistance with this piece.

Originally appeared in Prism, the BFS Newsletter, Vol. 23, No. 1, Jan/Feb 1999. Reprinted by permission.

![The Man Who Knew Too Much – 4K restoration / Blu-ray [A]](http://www.bernardherrmann.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/TMWKTM-4K.jpeg)

![The Bride Wore Black / Blu-ray [B]](http://www.bernardherrmann.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/07/BrideWoreBlack.jpeg)

![Alfred Hitchcock Classics Collection / Blu-ray [A,B]](http://www.bernardherrmann.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/AHClassics1.jpg)

![Endless Night (US Blu-ray) / Blu-ray [A]](http://www.bernardherrmann.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/EndlessNightUS.jpg)

![Endless Night (UK Blu-ray) / Blu-ray [B]](http://www.bernardherrmann.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/12/ENightBluRay.jpg)